John Blakey explores the FACTS coaching model – this month looks at ‘T’ for ‘Tension’.

Topics such as feedback, accountability, challenge, tension and systems thinking are all relevant to the role of a coach in delivering great ‘bottom line’ results – particularly in an economic environment where buyers of executive coaching are asking awkward questions like ‘Where were all the coaches when the banks went down?’. At 121partners, we have coined the acronym ‘FACTS’ to summarise these ‘tough love’ skills and apply them to support organisations where the emphasis is now on using coaching to support ‘organisational needs’ rather than ‘individual wants’. In this third article, we will focus upon ‘T’ for tension.

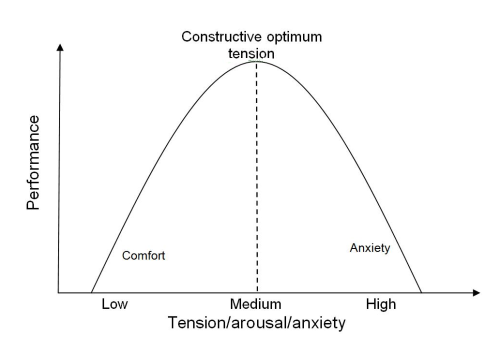

The “T” in the FACTS approach is possibly the hardest skill for the coach to master and yet is critical to gaining the optimum performance outcome from coaching. Tension can also be described as arousal or anxiety. As tension increases, performance increases to an optimum level and then tails off. The relationship between arousal and performance (the Yerkes-Dodson law), was identified by two psychologists in 1908 (Yerkes & Dodson, 1908). This relationship is shown in the graph below :

Their Yerkes-Dodson law demonstrates that performance increases with physiological or mental arousal up to an optimal level and then tails off. It can be said that there are two halves to the performance-tension curve. The left half of the inverted ‘U’ is the energising effect of arousal, while the right half represents the negative effects of over-arousal such as stress.

Getting the right ‘tension’

Sometimes there is a negative interpretation of the word tension. Tension has become associated with stress and something that should be avoided. However, tension can also be thought of as potential energy. Imagine a rubber band that is stretched, as the tension of the band increases it holds more energy. Think about a child flicking a rubber band – the more the child stretches the band then the more tension there is and so, when the child releases the grip, the band flies through the air. If there is not enough energy, the band will flop to the floor. However, if the child stretches and stretches the band and does not release it, eventually the tension becomes too great and the band snaps.

So too is there an optimum level of tension in a coaching session, too little will not maximise performance and too much will lead to the client ‘snapping’. Coaching sessions with too little tension will be too comfortable and those with too much tension will result in a breakdown of the relationship. Neither extreme position maximises performance but inbetween there is the creative space for the coach to design the optimum tension specific to an individual coachee.

The implication for coaches is to examine their coaching and ask themselves if they are generating optimum levels of tension in each coaching session and if they are adapting these levels to suit the coachee’s scale of tension or their own. This awareness is important since many coaches believe tension should be low and sessions should be as relaxed as possible. One explanation for this is the link coaching has with the ‘sister’ profession of counselling. Typically people who go and see counsellors are declaring: “I’m not functioning properly and I want to feel better.” They are likely to have high levels of tension or anxiety and may already be in the sub-optimal area of the performance/tension graph. If this is the case, the counsellor will consciously create the conditions to reduce tension and anxiety and hold a relaxed session to restore the person to optimal performance. As a result, the amount of tension that a person in this state can take is much lower than your average senior executive in a major company who is functioning well and not in need of therapeutic input.

Many business leaders thrive on tension. So as coaches we’re talking about highly effective people who are not declared dysfunctional and can often take much more tension than coaches believe they can. Are you willing to work at levels of tension that may feel uncomfortable to you as the coach but are exactly what the coachee needs to achieve peak performance?

Silence is golden

Each coachee will have a natural starting point of arousal and tension. Each intervention by the coach will produce different levels of tension. Silence is one way of increasing the tension in a coaching session. Silence encourages the coachee to think deeper, to reflect more, and to be more creative. Others ways of increasing tension would be to use the feedback, challenge and accountability skills discussed in other aspects of the FACTS approach. Sometimes, it is simply a case of being prepared to disagree with the coachee, to not accept what they are saying or to change the tone and pace of the conversation.

For example, imagine a coaching session in which the coachee role played being the chief executive because he had to make a decision about a new way of structuring the organisation. The coach put the coachee in the chief executive’s position and said, “Okay, if it was your business, what would you do?” The coachee said, “I don’t know what I’d do,” to which the coach’s response was “You’ve got to make a decision – you’re the boss.” Following this intervention, the coach fell silent and allowed the tension in the session to rise as the coachee grappled with the ultimatum they had been given. Eventually, the coachee declared “I’ve got it! It is not about the structure at all. No structure would resolve this problem – we just need to work better as a team and that’s where I want to focus my energy.”

In this way, it can be seen that if coaches hold the view that tension is negative and should be avoided at all cost, they might be ‘selling their coachees short’. Can we afford to take such liberties when time are tough and all are required to ‘up their game’?

This article contains extracts from John Blakey and Ian Day’s recently published book ‘Where were all the coaches when the banks went down?’ which is available to order here. John can be contacted via info@121partners.com

For more background on the philosophy of the FACTS approach and its link to the question ‘Where all the coaches when the banks went down?’ see here and read Part 1: ‘F’ for Feedback, Part 2: ‘A’ for accountability and Part 3: ‘C’ for challenge.

John Blakey explores the FACTS coaching model - this month looks at 'T' for 'Tension'.

Topics such as feedback, accountability, challenge, tension and systems thinking are all relevant to the role of a coach in delivering great 'bottom line' results - particularly in an economic environment where buyers of executive coaching are asking awkward questions like 'Where were all the coaches when the banks went down?'. At 121partners, we have coined the acronym 'FACTS' to summarise these 'tough love' skills and apply them to support organisations where the emphasis is now on using coaching to support 'organisational needs' rather than 'individual wants'. In this third article, we will focus upon 'T' for tension.

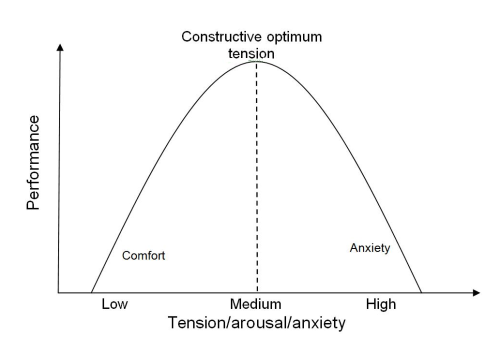

The “T” in the FACTS approach is possibly the hardest skill for the coach to master and yet is critical to gaining the optimum performance outcome from coaching. Tension can also be described as arousal or anxiety. As tension increases, performance increases to an optimum level and then tails off. The relationship between arousal and performance (the Yerkes-Dodson law), was identified by two psychologists in 1908 (Yerkes & Dodson, 1908). This relationship is shown in the graph below :

Their Yerkes-Dodson law demonstrates that performance increases with physiological or mental arousal up to an optimal level and then tails off. It can be said that there are two halves to the performance-tension curve. The left half of the inverted ‘U’ is the energising effect of arousal, while the right half represents the negative effects of over-arousal such as stress.

Getting the right 'tension'

Sometimes there is a negative interpretation of the word tension. Tension has become associated with stress and something that should be avoided. However, tension can also be thought of as potential energy. Imagine a rubber band that is stretched, as the tension of the band increases it holds more energy. Think about a child flicking a rubber band - the more the child stretches the band then the more tension there is and so, when the child releases the grip, the band flies through the air. If there is not enough energy, the band will flop to the floor. However, if the child stretches and stretches the band and does not release it, eventually the tension becomes too great and the band snaps.

So too is there an optimum level of tension in a coaching session, too little will not maximise performance and too much will lead to the client ‘snapping’. Coaching sessions with too little tension will be too comfortable and those with too much tension will result in a breakdown of the relationship. Neither extreme position maximises performance but inbetween there is the creative space for the coach to design the optimum tension specific to an individual coachee.

The implication for coaches is to examine their coaching and ask themselves if they are generating optimum levels of tension in each coaching session and if they are adapting these levels to suit the coachee’s scale of tension or their own. This awareness is important since many coaches believe tension should be low and sessions should be as relaxed as possible. One explanation for this is the link coaching has with the ‘sister’ profession of counselling. Typically people who go and see counsellors are declaring: “I'm not functioning properly and I want to feel better.” They are likely to have high levels of tension or anxiety and may already be in the sub-optimal area of the performance/tension graph. If this is the case, the counsellor will consciously create the conditions to reduce tension and anxiety and hold a relaxed session to restore the person to optimal performance. As a result, the amount of tension that a person in this state can take is much lower than your average senior executive in a major company who is functioning well and not in need of therapeutic input.

Many business leaders thrive on tension. So as coaches we're talking about highly effective people who are not declared dysfunctional and can often take much more tension than coaches believe they can. Are you willing to work at levels of tension that may feel uncomfortable to you as the coach but are exactly what the coachee needs to achieve peak performance?

Silence is golden

Each coachee will have a natural starting point of arousal and tension. Each intervention by the coach will produce different levels of tension. Silence is one way of increasing the tension in a coaching session. Silence encourages the coachee to think deeper, to reflect more, and to be more creative. Others ways of increasing tension would be to use the feedback, challenge and accountability skills discussed in other aspects of the FACTS approach. Sometimes, it is simply a case of being prepared to disagree with the coachee, to not accept what they are saying or to change the tone and pace of the conversation.

For example, imagine a coaching session in which the coachee role played being the chief executive because he had to make a decision about a new way of structuring the organisation. The coach put the coachee in the chief executive's position and said, “Okay, if it was your business, what would you do?” The coachee said, “I don't know what I'd do,” to which the coach's response was “You've got to make a decision - you're the boss.” Following this intervention, the coach fell silent and allowed the tension in the session to rise as the coachee grappled with the ultimatum they had been given. Eventually, the coachee declared “I've got it! It is not about the structure at all. No structure would resolve this problem - we just need to work better as a team and that's where I want to focus my energy.”

In this way, it can be seen that if coaches hold the view that tension is negative and should be avoided at all cost, they might be ‘selling their coachees short’. Can we afford to take such liberties when time are tough and all are required to ‘up their game’?

This article contains extracts from John Blakey and Ian Day's recently published book 'Where were all the coaches when the banks went down?' which is available to order here. John can be contacted via info@121partners.com

For more background on the philosophy of the FACTS approach and its link to the question 'Where all the coaches when the banks went down?' see here and read Part 1: 'F' for Feedback, Part 2: 'A' for accountability and Part 3: 'C' for challenge.