In the first of a series on social learning, The Internet Time Alliance explain some of the background of social learning and provide suggestions and advice on how to change thinking about learning to include social aspects.

Part 1: The Scaffolding

The social learning revolution has only just begun. Corporations that understand the value of knowledge sharing, teamwork, informal learning and joint problem solving are investing heavily in collaboration technology and are reaping the early rewards. – Jay Cross

Why is social learning important for today’s enterprise?

George Siemens, learning theorist and creator of Connectivism has elegantly explained the importance of social learning in the context of today’s workplace:

There is a growing demand for the ability to connect to others. It is with each other that we can make sense, and this is social. Organisations, in order to function, need to encourage social exchanges and social learning due to faster rates of business and technological changes. Social experience is adaptive by nature and a social learning mindset enables better feedback on environmental changes back to the organisation. – George Siemens

Together with our increased awareness of the need to adopt new approaches to supporting workers in doing their jobs, evidence is also telling us that a focus on knowledge transfer and acquisition, an approach rooted in Plato’s academy, is not the best one available to us. We need move to more discursive approaches to learning and development:

We are moving to the world of the sons of Socrates, where dialogue and guidance are key competencies. It is a world where the capability to find information and turn it into knowledge at the point-of-need provides the key competitive advantage, where knowing the right people to ask the right questions of is more likely to lead to success than any amount of internally-held knowledge and skill. – Charles Jennings

Our relationship with information and knowledge is changing as our work becomes more intangible and complex. Most of the value in today’s knowledge-based marketplace is intangible, with Google’s multi-billion dollar valuation an example of value in non-tangible processes that could be deflated with the development of a better search algorithm. Non-physical assets comprise about 80% of the value of Standard & Poor’s 500 US companies in leading industries. This is reflected in the rest of the developed, and developing, world.

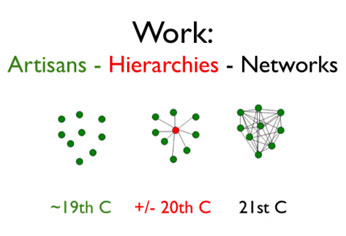

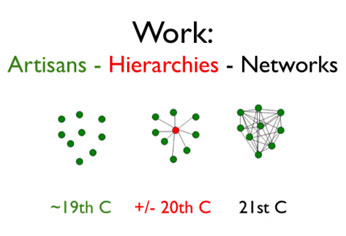

From replaceable human resources to dynamic social groups

The manner in which we prepare people for work is based on the Taylorist perspective that there is only one way to do a job, that knowledge is arranged vertically from superior down through subordinate roles and positions, and that the person doing the work needs to conform to job requirements [F.W. Taylor, The Principles of Scientific Management, 1911]. Individual training, the core of corporate learning and development, is based on the premise that jobs are relatively constant, the application of the necessary knowledge is the core requirement for effective performance, and those who fill the jobs are interchangeable.

However, when you look at the modern organisation, it is moving to a model of constant change, whether through mergers and acquisitions or as quick-start web-enabled networks. Competitors are moving faster, the rate of change is increasing, and problems and opportunities arise ever more frequently. For the Human Resources department, the question becomes one of preparing people for jobs that don’t even exist. For example, the role of online community manager, a fast-growing field today, barely existed five years ago. Individual training for job preparation requires a stable work environment. This is a luxury few have any more.

A collective, social learning approach, on the other hand, takes the perspective that learning and work happen as groups and how the group is connected (the network) is more important than any individual node within it.

A collective, social learning approach, on the other hand, takes the perspective that learning and work happen as groups and how the group is connected (the network) is more important than any individual node within it.Learning is both an individual and social activity, yet the vast majority of L&D departments focus only on the individual aspect. While they certainly should be focused on providing support for individual development, the majority of focus needs to be on creating and supporting the scaffolding for social learning.

Individual and social learning

MIT’s Peter Senge (creator of the ‘learning organisation’ concept) has clarified some terms we often use in looking at work, job classifications and the training to support them. We may think we all have a common understanding of these terms, but that’s not necessarily the case. Senge defined the key terms as follows:

Knowledge: the capacity for effective action. ‘Know-how’ is the only aspect of knowledge that really matters in life.

Practitioner: someone who is accountable for producing results.

Learning may be an individual activity but if it remains within the individual it is of no value whatsoever to the organisation. Acting on knowledge, as a practitioner (work performance) is all that matters.

Although Senge’s views do help align learning with results, these definitions are focused at individual learning rather than social learning. We would suggest modifying them as follows to take account of the core role that social learning plays:

Knowledge: the capacity for effective action (the ‘know-how’) plus the ‘know-who’ – knowing who to connect to in order to get work done is vital in a world continually challenged by change.

Practitioner: someone who is accountable for producing results regardless of whether they can do this individually or need to work with others to successfully complete the tasks.

Learning: a social activity where personal responsibility is a key factor.

The challenge to individual learning

So why are organisations in the individual learning (training) business anyway? Surely individuals should be directing their own learning. Organisations should focus on results.

Individual learning in organisations is considered to be basically irrelevant by some more enlightened practitioners because work is almost never done by one person. All organisational value is created by teams and networks. Certainly individuals make up the whole, but it is far better to focus on ensuring learning takes place as an integrated process for groups and for the entire organisation as a functioning organism rather than focusing on the constituent parts – individuals and transient teams. This is the approach taken by other disciplines. A good doctor, for instance, will treat organs and the whole body rather than individual cells. A cook will focus on the final taste and appearance of the dish rather than on the chemical constituents of the ingredients (unless, of course, the cook is Heston Blumenthal, whereby you will be served snail porridge or lickable wallpaper).

The importance of social networks

Learning may well be generated in teams but even this type of knowledge comes and goes as teams are formed and disbanded. Learning really spreads through engagement in and with social networks. Social networks are the primary conduit for effective organisational performance. Blocking, or circumventing, social networks slows learning, reduces effectiveness and may in the end kill the organisation.

Social learning is how groups work and share knowledge to become better practitioners. Organisations need to focus on enabling practitioners to produce results by supporting learning through social networks. The rest is just window dressing. Over a century ago, Charles Darwin helped us understand the importance of adaptation and the concept that those who survive are the ones who most accurately perceive their environment and successfully adapt to it. Co-operating in networks can increase our ability to perceive what is happening.

This is Part 1 of a four-part series of articles on the September theme of Social Learning. The series has been authored by members of the Internet Time Alliance (ITA) and other colleagues. ITA members are Jay Cross, Jane Hart, Jon Husband, Harold Jarche, Charles Jennings and Clark Quinn.

The Internet Time Alliance is a group of six leading experts with more than a century of experience managing projects, designing interventions, improving service, increasing sales, and boosting profits. ITA members who have contributed to this post include Jay Cross, Jane Hart, Jon Husband, Harold Jarche, Charles Jennings and Clark Quinn.

In the first of a series on social learning, The Internet Time Alliance explain some of the background of social learning and provide suggestions and advice on how to change thinking about learning to include social aspects.

Part 1: The Scaffolding

The social learning revolution has only just begun. Corporations that understand the value of knowledge sharing, teamwork, informal learning and joint problem solving are investing heavily in collaboration technology and are reaping the early rewards. - Jay Cross

Why is social learning important for today’s enterprise?

George Siemens, learning theorist and creator of Connectivism has elegantly explained the importance of social learning in the context of today’s workplace:

There is a growing demand for the ability to connect to others. It is with each other that we can make sense, and this is social. Organisations, in order to function, need to encourage social exchanges and social learning due to faster rates of business and technological changes. Social experience is adaptive by nature and a social learning mindset enables better feedback on environmental changes back to the organisation. - George Siemens

Together with our increased awareness of the need to adopt new approaches to supporting workers in doing their jobs, evidence is also telling us that a focus on knowledge transfer and acquisition, an approach rooted in Plato's academy, is not the best one available to us. We need move to more discursive approaches to learning and development:

We are moving to the world of the sons of Socrates, where dialogue and guidance are key competencies. It is a world where the capability to find information and turn it into knowledge at the point-of-need provides the key competitive advantage, where knowing the right people to ask the right questions of is more likely to lead to success than any amount of internally-held knowledge and skill. - Charles Jennings

Our relationship with information and knowledge is changing as our work becomes more intangible and complex. Most of the value in today's knowledge-based marketplace is intangible, with Google's multi-billion dollar valuation an example of value in non-tangible processes that could be deflated with the development of a better search algorithm. Non-physical assets comprise about 80% of the value of Standard & Poor's 500 US companies in leading industries. This is reflected in the rest of the developed, and developing, world.

From replaceable human resources to dynamic social groups

The manner in which we prepare people for work is based on the Taylorist perspective that there is only one way to do a job, that knowledge is arranged vertically from superior down through subordinate roles and positions, and that the person doing the work needs to conform to job requirements [F.W. Taylor, The Principles of Scientific Management, 1911]. Individual training, the core of corporate learning and development, is based on the premise that jobs are relatively constant, the application of the necessary knowledge is the core requirement for effective performance, and those who fill the jobs are interchangeable.

However, when you look at the modern organisation, it is moving to a model of constant change, whether through mergers and acquisitions or as quick-start web-enabled networks. Competitors are moving faster, the rate of change is increasing, and problems and opportunities arise ever more frequently. For the Human Resources department, the question becomes one of preparing people for jobs that don't even exist. For example, the role of online community manager, a fast-growing field today, barely existed five years ago. Individual training for job preparation requires a stable work environment. This is a luxury few have any more.

A collective, social learning approach, on the other hand, takes the perspective that learning and work happen as groups and how the group is connected (the network) is more important than any individual node within it.

A collective, social learning approach, on the other hand, takes the perspective that learning and work happen as groups and how the group is connected (the network) is more important than any individual node within it.Learning is both an individual and social activity, yet the vast majority of L&D departments focus only on the individual aspect. While they certainly should be focused on providing support for individual development, the majority of focus needs to be on creating and supporting the scaffolding for social learning.

Individual and social learning

MIT's Peter Senge (creator of the 'learning organisation' concept) has clarified some terms we often use in looking at work, job classifications and the training to support them. We may think we all have a common understanding of these terms, but that's not necessarily the case. Senge defined the key terms as follows:

Knowledge: the capacity for effective action. 'Know-how' is the only aspect of knowledge that really matters in life.

Practitioner: someone who is accountable for producing results.

Learning may be an individual activity but if it remains within the individual it is of no value whatsoever to the organisation. Acting on knowledge, as a practitioner (work performance) is all that matters.

Although Senge's views do help align learning with results, these definitions are focused at individual learning rather than social learning. We would suggest modifying them as follows to take account of the core role that social learning plays:

Knowledge: the capacity for effective action (the 'know-how') plus the 'know-who' - knowing who to connect to in order to get work done is vital in a world continually challenged by change.

Practitioner: someone who is accountable for producing results regardless of whether they can do this individually or need to work with others to successfully complete the tasks.

Learning: a social activity where personal responsibility is a key factor.

The challenge to individual learning

So why are organisations in the individual learning (training) business anyway? Surely individuals should be directing their own learning. Organisations should focus on results.

Individual learning in organisations is considered to be basically irrelevant by some more enlightened practitioners because work is almost never done by one person. All organisational value is created by teams and networks. Certainly individuals make up the whole, but it is far better to focus on ensuring learning takes place as an integrated process for groups and for the entire organisation as a functioning organism rather than focusing on the constituent parts – individuals and transient teams. This is the approach taken by other disciplines. A good doctor, for instance, will treat organs and the whole body rather than individual cells. A cook will focus on the final taste and appearance of the dish rather than on the chemical constituents of the ingredients (unless, of course, the cook is Heston Blumenthal, whereby you will be served snail porridge or lickable wallpaper).

The importance of social networks

Learning may well be generated in teams but even this type of knowledge comes and goes as teams are formed and disbanded. Learning really spreads through engagement in and with social networks. Social networks are the primary conduit for effective organisational performance. Blocking, or circumventing, social networks slows learning, reduces effectiveness and may in the end kill the organisation.

Social learning is how groups work and share knowledge to become better practitioners. Organisations need to focus on enabling practitioners to produce results by supporting learning through social networks. The rest is just window dressing. Over a century ago, Charles Darwin helped us understand the importance of adaptation and the concept that those who survive are the ones who most accurately perceive their environment and successfully adapt to it. Co-operating in networks can increase our ability to perceive what is happening.

This is Part 1 of a four-part series of articles on the September theme of Social Learning. The series has been authored by members of the Internet Time Alliance (ITA) and other colleagues. ITA members are Jay Cross, Jane Hart, Jon Husband, Harold Jarche, Charles Jennings and Clark Quinn.

The Internet Time Alliance is a group of six leading experts with more than a century of experience managing projects, designing interventions, improving service, increasing sales, and boosting profits. ITA members who have contributed to this post include Jay Cross, Jane Hart, Jon Husband, Harold Jarche, Charles Jennings and Clark Quinn.