To understand what makes elearning work or fail we must look at the way learners learn and what motivates us to learn, says Alan Nelson.

When I was asked to speak at the Learning Technologies conference about good and bad elearning, I balked at the brief. I was being asked to describe “good” and “bad” and show examples of each. Why would I stick my head above the parapet in that way? Well, apparently someone had to do it and as the current elearning development company of the year, the job fell to us. So what does distinguish good from bad? Firstly a couple of observations from our work over the last ten years.

Observation 1: We are all different

Every adult professional learner comes to a particular learning resource with their own unique perspective. Take two accountants both registering for a course on practice management.

" Developers have unwittingly colluded with reluctant learners in providing resources that allow them to engage at the lowest possible level."

Developers have unwittingly colluded with reluctant learners in providing resources that allow them to engage at the lowest possible level."

The tendency is to treat them the same, but one may be recently qualified while the other has been practising for years. One may be in practice and the other working for a large company in their finance department. One may like to learn in a collaborative way, sharing their experiences with their peers, while the other is looking for the authority of the author. One may be an expert in corporation tax while the other is a generalist. The course may be relevant to both, but if you try to force them both down the same route without respecting their prior knowledge and experience, both will be alienated. Complicating things further though, is . . .

Observation 2: We are not consistent about the way in which we are different

As we move from one experience to another, our behaviour changes. While we are confident in one situation we may become more cautious elsewhere, perhaps where we are less experienced, or dealing with something that we don’t feel plays to our strengths. Caution changes our learning style, making us less prepared to dive in and have a go. Learning resources need to accommodate this, enabling learners to pick their way through materials as they go, in a way that works best for them.

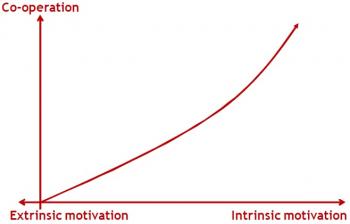

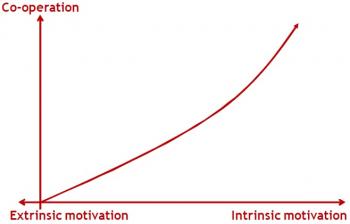

In particular we have noticed that the reason people come to a piece of learning affects their attitude and behaviour. In the case of intrinsic motivation, where the desire to learn comes from the individual and they are looking for greater personal or professional enlightenment, they tend to be open minded, enthusiastic and prepared to cooperate, both with what they are being asked to do and with each other.

Contrast that with extrinsic motivation, where the individual is being instructed to complete a piece of learning, and the level of co-operation is much lower. We asked a group of bankers, completing a compliance course, how they would prefer to learn. “Not at all” came the resounding reply. “We’re only here because we have no choice.” Our attempts to meet them half way by accommodating different learning styles were stymied by their lack of enthusiasm for personal engagement.

This is important because compliance work makes up so much of the elearning industry’s output. It is critical that we don’t give up on trying to create engaging learning resources that put the individual learner in control. But that means persuading them to engage rather than simply comply.

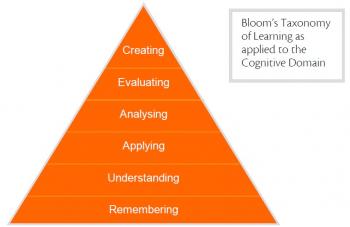

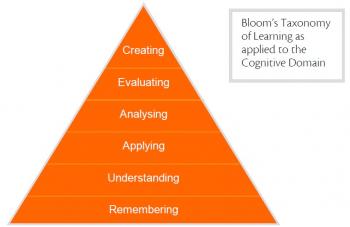

This is Bloom’s taxonomy as applied to the cognitive domain – remembering things. Surely the reason why so much elearning has never gone above the bottom two levels of the diagram is that developers have unwittingly colluded with reluctant learners in providing resources that allow them to engage at the lowest possible level.

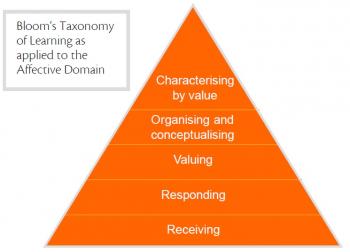

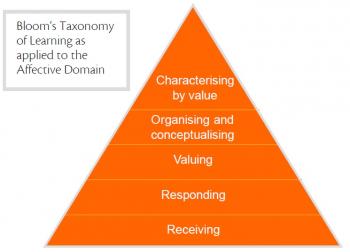

We should be setting the bar much higher, not only by looking at the upper levels of this diagram but by considering Bloom’s much less widely cited taxonomy of learning as applied to the affective domain – the bit

that attempts to explain the way people react emotionally. This is far more relevant in any efforts to change attitudes and behaviour.

We have done a lot of work on competition compliance and have found that in fact you can write down on a side of A4 everything the average manager needs to know about price fixing. What matters is not that they can recite the law but that they really change their attitudes and behaviour. We won’t achieve this by telling them stuff and then testing their retention, and we won’t get them to higher levels of engagement unless we can break through their general cussedness when being compelled to do something.

This isn’t a new problem. Almost 25 years ago two researchers, Malone and Lepper, looking at factors affecting intrinsic motivation, said: “It seems a frequent assumption that learning is boring and unpleasant drudgery – something one endures only to avoid punishment or to achieve some eternal goal, such as a high-paying job.”

I don’t have to twist that very much to come up with: “It seems a frequent assumption that elearning is boring and unpleasant drudgery – something one endures only to avoid punishment or to achieve some external goal, such as a high-paying job or to stop the compliance officer sending annoying e-mails.”

So what was Malone and Lepper’s answer? They came up with seven factors affecting intrinsic motivation:

- Challenge

- Curiosity

- Control

- Fantasy

- Competition

- Cooperation

- Recognition.

Let’s look at them in turn.

Challenge

People are motivated . . . when they are working towards personally meaningful goals.

The key here is that the goals must be personally meaningful. So introducing a topic with the words “After completing this course, you will be able to…..” is unlikely to help. People need to explore for themselves what they want to or need to learn. Ask them questions about their objectives and their experience and knowledge and make suggestions about possible routes through the material. Be careful to frame these diagnostic tools as a help to their decisions, not as something that makes the decision for them.

Curiosity

People are motivated ….. by the discrepancy between present knowledge or skills and what could be achieved.

Formative tests can help here – self assessments that they can complete before they start to identify their own strengths and weaknesses.

Control

People are motivated ….. when they can control what happens to them.

And that means more than simply allowing them to click on the next button.

Fantasy

People are motivated ….. when they can imagine relating what they are learning to real life settings.

This sounds like a grand term, but its application can be quite simple. In our award winning course for One Plus One, which helps health professionals to counsel couples on relationship issues, we finish a module introducing several theoretical models with a simple exercise: “Think about a client you’ve worked with. How do these models shed light on what is going on in the relationship?”

Competition

People are motivated ….. when they can compare their performance favourably to others.

Our experience is that assessments are more powerful when they focus on comparative performance rather than on whether you have “passed”. In fact, even where the comparison to others is not favourable, we see a positive impact on motivation.

Co-operation

People are motivated . . . when they can feel satisfaction from helping others.

Participation in activities requiring thoughtful prose answers increases significantly when people know that their answer will be shared with other learners. We asked learners on a fundraising course to tell us what inspired them about fundraising. We then shared their answers, creating an activity where much of the value came from the peer group.

Recognition

People are motivated . . . when others recognise and appreciate their accomplishments.

Nothing undermines motivation more than feeling ignored and isolated. Enabling people to highlight contributions from others creates the possibility for peer approval, and public acknowledgement from a tutor is a powerful tool in maintaining enthusiasm and commitment.

It all sounds quite simple. So why is so much elearning still so poor? Here are three lessons to be learned from three common pitfalls:

1. "If it was already a bit crap, putting it online won’t make it better!"

We publish a wide range of CPD courses for accountants, designed to enable them to stay up to date and complete the hours of learning required by their professional body. Our competitors in that world haven’t read Malone and Lepper. Their offerings mostly constitute streamed video of lectures by experts on various topics. Now I have never been a fan of lectures in the first place and these experts are some of the worst lecturers I have ever seen. Watching them has led us to coin this first lesson.

2. "Just because it works well in a different medium, doesn’t mean it should work like that online."

On the other hand, sometimes it is clear that the online course is based on a pre-existing face-to-face course that was good. The developers are keen not to lose the essence of the original experience. They often focus particularly on the personality of the presenter. They capture video and play it in a window alongside interactive text and graphics that illustrate the points being made. But almost always the finished product gets lower ratings than the original. In fact all you can ever really hope to achieve is to be as almost good as the original.

3. "Putting people in control means more than just letting them click the next button!"

One of my colleagues is a school governor. She recently agreed to complete an elearning course called “Safer Recruitment”. She logged on, personally interested in being a good governor, and professionally interested in what the developer had put together. On the first screen she was greeted by the message “Screen 1 of 258”. (I am not exaggerating!) So I would have hoped not to have to include this here, but it appears still to be necessary.

Summary

At Nelson Croom we have always set our stall out by emphasising the importance of focusing on the individual learner. In the end, it comes down to the simple phrase: “It’s about learning, not teaching.”

The seven pointers from Malone and Lepper remain as relevant today as they were twenty-five years ago and the three simple lessons I have included should help you to avoid some of the main pitfalls.

I’ll end with this quick checklist of what to my mind distinguishes good from bad elearning. As for the ugly, perhaps that is in the eye of the beholder.

Alan Nelson is co-founder and managing director of Nelson Croom, the E-Learning Awards’ E-Learning development company of the year. Alan works with clients to help them take advantage of the opportunities that online learning presents. His focus is on the finance, legal, general professional services and publishing industries.

To understand what makes elearning work or fail we must look at the way learners learn and what motivates us to learn, says Alan Nelson.

When I was asked to speak at the Learning Technologies conference about good and bad elearning, I balked at the brief. I was being asked to describe “good” and “bad” and show examples of each. Why would I stick my head above the parapet in that way? Well, apparently someone had to do it and as the current elearning development company of the year, the job fell to us. So what does distinguish good from bad? Firstly a couple of observations from our work over the last ten years.

Observation 1: We are all different

Every adult professional learner comes to a particular learning resource with their own unique perspective. Take two accountants both registering for a course on practice management.

" Developers have unwittingly colluded with reluctant learners in providing resources that allow them to engage at the lowest possible level."

Developers have unwittingly colluded with reluctant learners in providing resources that allow them to engage at the lowest possible level." The tendency is to treat them the same, but one may be recently qualified while the other has been practising for years. One may be in practice and the other working for a large company in their finance department. One may like to learn in a collaborative way, sharing their experiences with their peers, while the other is looking for the authority of the author. One may be an expert in corporation tax while the other is a generalist. The course may be relevant to both, but if you try to force them both down the same route without respecting their prior knowledge and experience, both will be alienated. Complicating things further though, is . . .

Observation 2: We are not consistent about the way in which we are different

As we move from one experience to another, our behaviour changes. While we are confident in one situation we may become more cautious elsewhere, perhaps where we are less experienced, or dealing with something that we don’t feel plays to our strengths. Caution changes our learning style, making us less prepared to dive in and have a go. Learning resources need to accommodate this, enabling learners to pick their way through materials as they go, in a way that works best for them.

In particular we have noticed that the reason people come to a piece of learning affects their attitude and behaviour. In the case of intrinsic motivation, where the desire to learn comes from the individual and they are looking for greater personal or professional enlightenment, they tend to be open minded, enthusiastic and prepared to cooperate, both with what they are being asked to do and with each other.

Contrast that with extrinsic motivation, where the individual is being instructed to complete a piece of learning, and the level of co-operation is much lower. We asked a group of bankers, completing a compliance course, how they would prefer to learn. “Not at all” came the resounding reply. “We’re only here because we have no choice.” Our attempts to meet them half way by accommodating different learning styles were stymied by their lack of enthusiasm for personal engagement.

This is important because compliance work makes up so much of the elearning industry’s output. It is critical that we don’t give up on trying to create engaging learning resources that put the individual learner in control. But that means persuading them to engage rather than simply comply.

This is Bloom’s taxonomy as applied to the cognitive domain – remembering things. Surely the reason why so much elearning has never gone above the bottom two levels of the diagram is that developers have unwittingly colluded with reluctant learners in providing resources that allow them to engage at the lowest possible level.

We should be setting the bar much higher, not only by looking at the upper levels of this diagram but by considering Bloom’s much less widely cited taxonomy of learning as applied to the affective domain – the bit

that attempts to explain the way people react emotionally. This is far more relevant in any efforts to change attitudes and behaviour.

We have done a lot of work on competition compliance and have found that in fact you can write down on a side of A4 everything the average manager needs to know about price fixing. What matters is not that they can recite the law but that they really change their attitudes and behaviour. We won’t achieve this by telling them stuff and then testing their retention, and we won’t get them to higher levels of engagement unless we can break through their general cussedness when being compelled to do something.

This isn’t a new problem. Almost 25 years ago two researchers, Malone and Lepper, looking at factors affecting intrinsic motivation, said: “It seems a frequent assumption that learning is boring and unpleasant drudgery – something one endures only to avoid punishment or to achieve some eternal goal, such as a high-paying job.”

I don’t have to twist that very much to come up with: “It seems a frequent assumption that elearning is boring and unpleasant drudgery – something one endures only to avoid punishment or to achieve some external goal, such as a high-paying job or to stop the compliance officer sending annoying e-mails.”

So what was Malone and Lepper’s answer? They came up with seven factors affecting intrinsic motivation:

- Challenge

- Curiosity

- Control

- Fantasy

- Competition

- Cooperation

- Recognition.

Let’s look at them in turn.

Challenge

People are motivated . . . when they are working towards personally meaningful goals.

The key here is that the goals must be personally meaningful. So introducing a topic with the words “After completing this course, you will be able to.....” is unlikely to help. People need to explore for themselves what they want to or need to learn. Ask them questions about their objectives and their experience and knowledge and make suggestions about possible routes through the material. Be careful to frame these diagnostic tools as a help to their decisions, not as something that makes the decision for them.

Curiosity

People are motivated ..... by the discrepancy between present knowledge or skills and what could be achieved.

Formative tests can help here - self assessments that they can complete before they start to identify their own strengths and weaknesses.

Control

People are motivated ..... when they can control what happens to them.

And that means more than simply allowing them to click on the next button.

Fantasy

People are motivated ..... when they can imagine relating what they are learning to real life settings.

This sounds like a grand term, but its application can be quite simple. In our award winning course for One Plus One, which helps health professionals to counsel couples on relationship issues, we finish a module introducing several theoretical models with a simple exercise: “Think about a client you’ve worked with. How do these models shed light on what is going on in the relationship?”

Competition

People are motivated ..... when they can compare their performance favourably to others.

Our experience is that assessments are more powerful when they focus on comparative performance rather than on whether you have “passed”. In fact, even where the comparison to others is not favourable, we see a positive impact on motivation.

Co-operation

People are motivated . . . when they can feel satisfaction from helping others.

Participation in activities requiring thoughtful prose answers increases significantly when people know that their answer will be shared with other learners. We asked learners on a fundraising course to tell us what inspired them about fundraising. We then shared their answers, creating an activity where much of the value came from the peer group.

Recognition

People are motivated . . . when others recognise and appreciate their accomplishments.

Nothing undermines motivation more than feeling ignored and isolated. Enabling people to highlight contributions from others creates the possibility for peer approval, and public acknowledgement from a tutor is a powerful tool in maintaining enthusiasm and commitment.

It all sounds quite simple. So why is so much elearning still so poor? Here are three lessons to be learned from three common pitfalls:

1. "If it was already a bit crap, putting it online won’t make it better!"

We publish a wide range of CPD courses for accountants, designed to enable them to stay up to date and complete the hours of learning required by their professional body. Our competitors in that world haven’t read Malone and Lepper. Their offerings mostly constitute streamed video of lectures by experts on various topics. Now I have never been a fan of lectures in the first place and these experts are some of the worst lecturers I have ever seen. Watching them has led us to coin this first lesson.

2. "Just because it works well in a different medium, doesn’t mean it should work like that online."

On the other hand, sometimes it is clear that the online course is based on a pre-existing face-to-face course that was good. The developers are keen not to lose the essence of the original experience. They often focus particularly on the personality of the presenter. They capture video and play it in a window alongside interactive text and graphics that illustrate the points being made. But almost always the finished product gets lower ratings than the original. In fact all you can ever really hope to achieve is to be as almost good as the original.

3. "Putting people in control means more than just letting them click the next button!"

One of my colleagues is a school governor. She recently agreed to complete an elearning course called “Safer Recruitment”. She logged on, personally interested in being a good governor, and professionally interested in what the developer had put together. On the first screen she was greeted by the message “Screen 1 of 258”. (I am not exaggerating!) So I would have hoped not to have to include this here, but it appears still to be necessary.

Summary

At Nelson Croom we have always set our stall out by emphasising the importance of focusing on the individual learner. In the end, it comes down to the simple phrase: “It’s about learning, not teaching.”

The seven pointers from Malone and Lepper remain as relevant today as they were twenty-five years ago and the three simple lessons I have included should help you to avoid some of the main pitfalls.

I’ll end with this quick checklist of what to my mind distinguishes good from bad elearning. As for the ugly, perhaps that is in the eye of the beholder.

Alan Nelson is co-founder and managing director of Nelson Croom, the E-Learning Awards’ E-Learning development company of the year. Alan works with clients to help them take advantage of the opportunities that online learning presents. His focus is on the finance, legal, general professional services and publishing industries.

Developers have unwittingly colluded with reluctant learners in providing resources that allow them to engage at the lowest possible level."

Developers have unwittingly colluded with reluctant learners in providing resources that allow them to engage at the lowest possible level."

Developers have unwittingly colluded with reluctant learners in providing resources that allow them to engage at the lowest possible level."

Developers have unwittingly colluded with reluctant learners in providing resources that allow them to engage at the lowest possible level."