Our memory and power of recall detriorates rapidly if we do not reinforce what we have learnt. Garry Platt looks at the implications for training design and delivery.

In 1895 Herman Ebbinghaus published some fascinating research which many people in the training community diligently ignore or are simply unfamiliar with. This is strange as it has significant and direct implications on how we design and then deliver learning, training or development. It also underpins the ultimate effectiveness and results that we obtain as professional developers and trainers.

In his book Memory: A Contribution to Experimental Psychology, Herman Ebbinghaus presented the findings of a study he conducted into memory and recall, from this work has stemmed the term The Forgetting Curve.

This work despite being more than 100 years old is still pertinent today and is complimented by current research (J. D. Karpicke, J. R. Blunt. "Spacing Effects in Learning: A Temporal Ridgeline of Optimal Retention." Psychological Science, 19, 1095-1102. November 1, 2008). So what is a forgetting curve? Ebbinghaus through his investigation tried to identify how quickly memory deteriorates if nothing is done to reinforce it. Reduced retention can lead to reduced learning.

It is important to understand that today we recognise different forms of memory and indeed many variants of the nature of that memory. Ebbinghaus focused on the recall of simple lists of unrelated nonsense words. In the workplace this is unlikely to be the content or process of learning, never the less his findings are interesting.

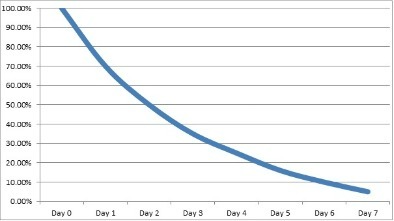

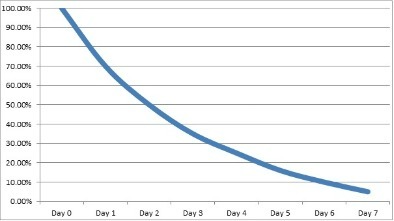

Ebbinghaus discovered that even with this simple task memory failed at an alarming rate. His findings are often illustrated by a graph showing how memory and recall deteriorates over a short space of time. The X axis (horizontal) measuring time and the Y axis (vertical) measuring recall.

This graph or ones similar often appear in books and websites but do not always reflect Ebbinghaus’s actual results. His research indicated that total recall (100%) for him was achieved only at the time of acquisition. Following that, retention dropped away very quickly:

- Within 20 minutes 42% of the memorised list was lost.

- Within 24 hours 67% of what he learned had vanished.

- A month later 79% had been forgotten with a meagre 21% retention.

It is evident that the Ebbinghaus experiments related to a very specific type of memory and content. However it is still true that for most individuals memory degrades if the content is not revisited and reinforced. The rate of deterioration may be different from the figures Ebbinghaus published but it is frequently faster than we may at first think.

For some people this issue is difficult to accept and frequently they cite their own experience of knowledge retention. I recognise this criticism. The individuals are convinced that they have much better recall than is being alluded to here.

"Exercises and activities aimed at reviewing and revisiting learnt content can be beneficial to improving retention and recall."

"Exercises and activities aimed at reviewing and revisiting learnt content can be beneficial to improving retention and recall."Geralda Odinot of Leiden University undertaking contemporary research in crime witness testimony (Odinot, G. (2008). Eyewitness confidence: The relation between accuracy and confidence in episodic memory. Doctoral dissertation, University of Leiden, Leiden, The Netherlands [ISBN 978 90 79969 01 2]) proposes however that recall is no evidence of reliability. Huge amounts of recalled information given by witnesses is in fact imagined and wholly false. The individual concerned believes their testimony is both a true and correct reflection of what they saw and observed.

Whilst this is a long way from the classroom or e-based learning environment I suspect many of the same factors are at play. Doubtless some of you have had questions asked some time after a training session where what was raised or outlined indicates a hideously mangled and/or totally unsound grasp of the topic covered. Despite the fact that at the time both they and you thought they had learnt and understood the material.

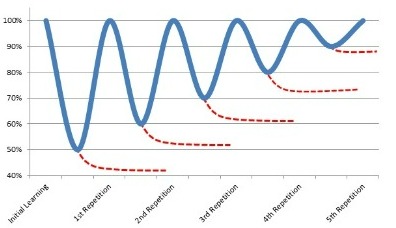

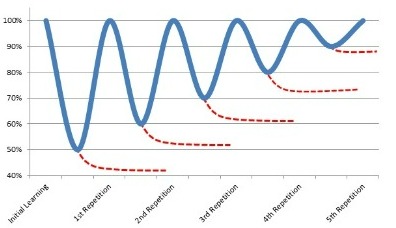

One of the biggest aids to increasing retention (though by no means the only aid) is repetition. The review of learnt material, the revisiting of content which has previously been covered. By introducing repetition learning may not necessarily be enhanced but retention most certainly will. This process is again frequently illustrated by a graph similar to the following.

But again these figures do not represent the research that Ebbinghaus produced, but do represent the concept he was proposing in chapter eight of his work, Retention as a function of repeated learning. Put simply: each revisiting of learnt material reinforces its retention.

What does this mean for trainers and developers? It means exercises and activities aimed at reviewing and revisiting learnt content can be beneficial to improving retention and recall. As part of a standard lesson plan for whatever medium a process of revision is appropriate and helpful to learners. It is often seen as a challenge by deliverers as they have so much content they must cover in a limited time.

I have found that group exercises which get the candidates to capture or illustrate all the learning content they can remember is an immensely useful activity as it allows me to see their understanding and identify the individuals who have not got such a strong grasp of the content. The group process of reviewing helps them to help each other with their memory and understanding. Towards the end of programmes it can also be a useful process to get learners to collate and present back to everyone the key concepts and learning from the programme, once again effectively reviewing and revisiting the material.

Another important strategy is to get learners after the developmental process to revisit the material. At a very basic level I have used assignments requiring the presentation of theory contextualised to their workplace and I have set up conference calls to undertake a simple discussion and refocus on content. More powerfully I have used action learning sets.

It has been suggested that learning should be revisited at least two to three times before we begin to see significant retention and recall. The options to achieve this are many but seldom used and the result is lost learning. The issue is straightforward, people will inevitable forget what you train and teach them unless they get the opportunity to revisit, review or revise the content addressed by the programme.

Academically qualified to Masters Degree level in Education, Training and Development his work combines current research and study in Human Resource Development with a pragmatic and workable approach. Visit the EEF website for further details. Gary writes the Platts Puzzlings blog here on TrainingZone as well as managing the Transactional Analysis discussion group.

Our memory and power of recall detriorates rapidly if we do not reinforce what we have learnt. Garry Platt looks at the implications for training design and delivery.

In 1895 Herman Ebbinghaus published some fascinating research which many people in the training community diligently ignore or are simply unfamiliar with. This is strange as it has significant and direct implications on how we design and then deliver learning, training or development. It also underpins the ultimate effectiveness and results that we obtain as professional developers and trainers.

In his book Memory: A Contribution to Experimental Psychology, Herman Ebbinghaus presented the findings of a study he conducted into memory and recall, from this work has stemmed the term The Forgetting Curve.

This work despite being more than 100 years old is still pertinent today and is complimented by current research (J. D. Karpicke, J. R. Blunt. "Spacing Effects in Learning: A Temporal Ridgeline of Optimal Retention." Psychological Science, 19, 1095-1102. November 1, 2008). So what is a forgetting curve? Ebbinghaus through his investigation tried to identify how quickly memory deteriorates if nothing is done to reinforce it. Reduced retention can lead to reduced learning.

It is important to understand that today we recognise different forms of memory and indeed many variants of the nature of that memory. Ebbinghaus focused on the recall of simple lists of unrelated nonsense words. In the workplace this is unlikely to be the content or process of learning, never the less his findings are interesting.

Ebbinghaus discovered that even with this simple task memory failed at an alarming rate. His findings are often illustrated by a graph showing how memory and recall deteriorates over a short space of time. The X axis (horizontal) measuring time and the Y axis (vertical) measuring recall.

This graph or ones similar often appear in books and websites but do not always reflect Ebbinghaus’s actual results. His research indicated that total recall (100%) for him was achieved only at the time of acquisition. Following that, retention dropped away very quickly:

- Within 20 minutes 42% of the memorised list was lost.

- Within 24 hours 67% of what he learned had vanished.

- A month later 79% had been forgotten with a meagre 21% retention.

It is evident that the Ebbinghaus experiments related to a very specific type of memory and content. However it is still true that for most individuals memory degrades if the content is not revisited and reinforced. The rate of deterioration may be different from the figures Ebbinghaus published but it is frequently faster than we may at first think.

For some people this issue is difficult to accept and frequently they cite their own experience of knowledge retention. I recognise this criticism. The individuals are convinced that they have much better recall than is being alluded to here.

"Exercises and activities aimed at reviewing and revisiting learnt content can be beneficial to improving retention and recall."

"Exercises and activities aimed at reviewing and revisiting learnt content can be beneficial to improving retention and recall."Geralda Odinot of Leiden University undertaking contemporary research in crime witness testimony (Odinot, G. (2008). Eyewitness confidence: The relation between accuracy and confidence in episodic memory. Doctoral dissertation, University of Leiden, Leiden, The Netherlands [ISBN 978 90 79969 01 2]) proposes however that recall is no evidence of reliability. Huge amounts of recalled information given by witnesses is in fact imagined and wholly false. The individual concerned believes their testimony is both a true and correct reflection of what they saw and observed.

Whilst this is a long way from the classroom or e-based learning environment I suspect many of the same factors are at play. Doubtless some of you have had questions asked some time after a training session where what was raised or outlined indicates a hideously mangled and/or totally unsound grasp of the topic covered. Despite the fact that at the time both they and you thought they had learnt and understood the material.

One of the biggest aids to increasing retention (though by no means the only aid) is repetition. The review of learnt material, the revisiting of content which has previously been covered. By introducing repetition learning may not necessarily be enhanced but retention most certainly will. This process is again frequently illustrated by a graph similar to the following.

But again these figures do not represent the research that Ebbinghaus produced, but do represent the concept he was proposing in chapter eight of his work, Retention as a function of repeated learning. Put simply: each revisiting of learnt material reinforces its retention.

What does this mean for trainers and developers? It means exercises and activities aimed at reviewing and revisiting learnt content can be beneficial to improving retention and recall. As part of a standard lesson plan for whatever medium a process of revision is appropriate and helpful to learners. It is often seen as a challenge by deliverers as they have so much content they must cover in a limited time.

I have found that group exercises which get the candidates to capture or illustrate all the learning content they can remember is an immensely useful activity as it allows me to see their understanding and identify the individuals who have not got such a strong grasp of the content. The group process of reviewing helps them to help each other with their memory and understanding. Towards the end of programmes it can also be a useful process to get learners to collate and present back to everyone the key concepts and learning from the programme, once again effectively reviewing and revisiting the material.

Another important strategy is to get learners after the developmental process to revisit the material. At a very basic level I have used assignments requiring the presentation of theory contextualised to their workplace and I have set up conference calls to undertake a simple discussion and refocus on content. More powerfully I have used action learning sets.

It has been suggested that learning should be revisited at least two to three times before we begin to see significant retention and recall. The options to achieve this are many but seldom used and the result is lost learning. The issue is straightforward, people will inevitable forget what you train and teach them unless they get the opportunity to revisit, review or revise the content addressed by the programme.

Academically qualified to Masters Degree level in Education, Training and Development his work combines current research and study in Human Resource Development with a pragmatic and workable approach. Visit the EEF website for further details. Gary writes the Platts Puzzlings blog here on TrainingZone as well as managing the Transactional Analysis discussion group.