Continuing their series on challenging coaching Ian Day and John Blakey, co-authors of ‘Challenging Coaching’, take a look at how to turn tension into a positive thing.

In this eighth article in the series on ‘Challenging Coaching’ and the FACTS coaching model we will focus upon the ‘T’ of FACTS, which stands for tension. Previous articles have addressed the principles of challenging coaching and the topics of feedback, accountability and courageous goals.

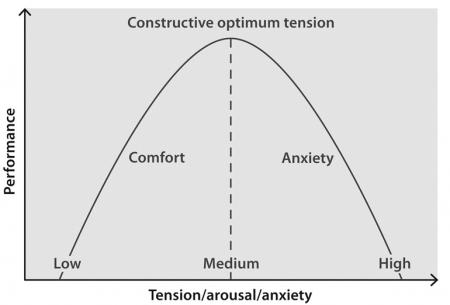

The ‘T’ in the FACTS approach is possibly the hardest skill for the coach to master and yet is critical to gaining the optimum performance outcome from coaching. Tension can also be described as arousal or anxiety. As tension increases, performance increases to an optimum level and then tails off. This relationship between anxiety and performance, known as the Yerkes-Dodson Law, was first identified by psychologists in 1908 and is shown in the diagram below :

Sometimes there is a negative interpretation of the word tension. Tension has become associated with stress and something that should be avoided. However, tension can also be thought of as potential energy. Think about a child stretching a rubber band – the more the child stretches the band then the more tension there is and so, when the child releases the grip, the band flies through the air. If there is not enough energy, the band will flop to the floor. However, if the child stretches the band too far eventually the tension becomes too great and the band snaps.

Similarly, too little tension in a coaching session will result in a ‘flop’, too much tension will result in the relationship ‘snapping’. The implication for coaches is to examine their coaching and ask themselves if they are generating optimum levels of tension in each coaching session and if they are adapting these levels to suit the coachee’s scale of tension not their own, i.e. aligned with the client’s Yerkes-Dodson curve. Many business leaders thrive on levels of tension higher than an average person. Are we willing to work at levels of tension that may feel uncomfortable to us as coaches but are exactly what the coachee needs to achieve peak performance?

Each coachee will have a natural starting point of arousal and tension. Each intervention by the coach will either raise the tension levels or reduce them. Here are some typical ways in which tension can be raised in a coaching conversation:

- Use of silence: the coach asks a question or makes a statement and lets the resulting silence do the ‘heavy lifting’

- Prolonged eye contact: eye contact can be supportive but prolonged eye contact can be intense, particularly when accompanying silence

- Probing questions: ‘what else?’, ‘what more could you do?’, ‘what are you avoiding?’

- Challenging statements: ‘I think you could aim higher than that…’, ‘that sounds too easy’, ‘I’m sure your boss is expecting more’

- Use an approach opposite to the coachee’s usual style – if the individual has a fast-paced, active approach the coach could adopt a slower, reflective style.

The interventions a coach can use to decrease tension are well documented in other articles and books and include active listening, acknowledging feelings, providing affirmation and building rapport.

In summary, it can be seen that if coaches hold the belief that tension is negative and should be avoided at all cost, they might be selling their coachees short. On the other hand, if we carefully calibrate tension and responsibly adjust levels of tension to suit the individual and their organisational context, then greater levels of performance are attainable. Can we afford to take the liberty of not exploring this possibility fully when times are tough and everyone is required to ‘up their game’?

Ian and John’s book ‘Challenging Coaching- Going beyond traditional coaching to face the FACTS’ published by Nicholas Brealey Publishing is available on Amazon. More resources can be accessed via www.challengingcoaching.co.uk. This is the eighth in a series of monthly columns on TrainingZone to explore the detail of challenging coaching

Continuing their series on challenging coaching Ian Day and John Blakey, co-authors of 'Challenging Coaching', take a look at how to turn tension into a positive thing.

In this eighth article in the series on 'Challenging Coaching' and the FACTS coaching model we will focus upon the 'T' of FACTS, which stands for tension. Previous articles have addressed the principles of challenging coaching and the topics of feedback, accountability and courageous goals.

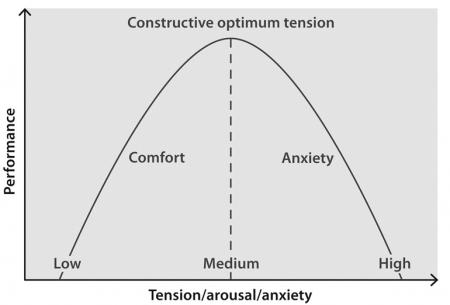

The 'T' in the FACTS approach is possibly the hardest skill for the coach to master and yet is critical to gaining the optimum performance outcome from coaching. Tension can also be described as arousal or anxiety. As tension increases, performance increases to an optimum level and then tails off. This relationship between anxiety and performance, known as the Yerkes-Dodson Law, was first identified by psychologists in 1908 and is shown in the diagram below :

Sometimes there is a negative interpretation of the word tension. Tension has become associated with stress and something that should be avoided. However, tension can also be thought of as potential energy. Think about a child stretching a rubber band - the more the child stretches the band then the more tension there is and so, when the child releases the grip, the band flies through the air. If there is not enough energy, the band will flop to the floor. However, if the child stretches the band too far eventually the tension becomes too great and the band snaps.

Similarly, too little tension in a coaching session will result in a 'flop', too much tension will result in the relationship 'snapping'. The implication for coaches is to examine their coaching and ask themselves if they are generating optimum levels of tension in each coaching session and if they are adapting these levels to suit the coachee's scale of tension not their own, i.e. aligned with the client's Yerkes-Dodson curve. Many business leaders thrive on levels of tension higher than an average person. Are we willing to work at levels of tension that may feel uncomfortable to us as coaches but are exactly what the coachee needs to achieve peak performance?

Each coachee will have a natural starting point of arousal and tension. Each intervention by the coach will either raise the tension levels or reduce them. Here are some typical ways in which tension can be raised in a coaching conversation:

- Use of silence: the coach asks a question or makes a statement and lets the resulting silence do the 'heavy lifting'

- Prolonged eye contact: eye contact can be supportive but prolonged eye contact can be intense, particularly when accompanying silence

- Probing questions: 'what else?', 'what more could you do?', 'what are you avoiding?'

- Challenging statements: 'I think you could aim higher than that...', 'that sounds too easy', 'I'm sure your boss is expecting more'

- Use an approach opposite to the coachee's usual style - if the individual has a fast-paced, active approach the coach could adopt a slower, reflective style.

The interventions a coach can use to decrease tension are well documented in other articles and books and include active listening, acknowledging feelings, providing affirmation and building rapport.

In summary, it can be seen that if coaches hold the belief that tension is negative and should be avoided at all cost, they might be selling their coachees short. On the other hand, if we carefully calibrate tension and responsibly adjust levels of tension to suit the individual and their organisational context, then greater levels of performance are attainable. Can we afford to take the liberty of not exploring this possibility fully when times are tough and everyone is required to 'up their game'?

Ian and John's book 'Challenging Coaching- Going beyond traditional coaching to face the FACTS' published by Nicholas Brealey Publishing is available on Amazon. More resources can be accessed via www.challengingcoaching.co.uk. This is the eighth in a series of monthly columns on TrainingZone to explore the detail of challenging coaching