Ian Day and John Blakey continue their series on challenging leadership. This time, the focus is on performance management.

“We need to get rid of David, he’s just not delivering. Sort it out for me” said the director to the human resources manager. In my former career in HR I remember several conversations that started like this. Talking to colleagues who are working in HR today, this type of conversation is still common. But what is going on here? It seems that the performance of an individual has dropped to a low level, issues have not been resolved. The person needs to be fired as the line manager is at the end of his tether. This could lead to an expensive payout and a compromise agreement.

In a similar situation I remember digging to find out what action the line manager had taken. Typically the responsibility for the breakdown in performance could be attributed 50:50 to the employee and line manager. Performance problems usually start when expectations are not explicit, feedback is absent and tricky conversations are avoided. In the example above, I remember the director saying “David is a senior professional, he should know what is expected, I don’t have time to spoon-feed him”.

So what causes these sort of situations and how can they be avoided?

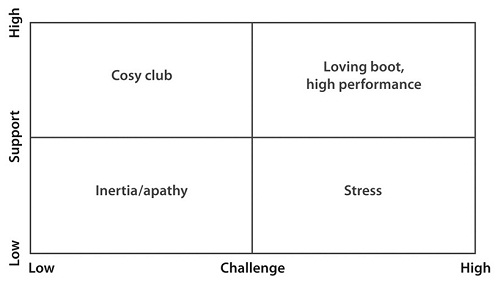

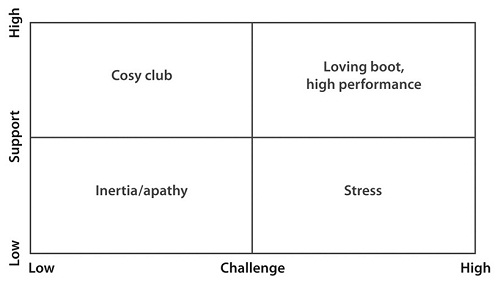

Consider the 2×2 support challenge matrix and in our example the line manager is in the inertia quadrant; not sure what to do, or too busy and hopes that the problem goes away. This is often followed by movement to the stress quadrant as the line manager loses his/her temper and angrily wants the person out of the business. However the ideal place is high performance high support, the loving boot quadrant of the matrix.

In this quadrant expectations are made explicit, assumptions are surfaced and clarified; difficult conversations are held early, avoiding escalation. The line manager must enter the ‘zone of uncomfortable debate’ so that the conversation moves into a more serious and tense discussion, honest feedback is exchanged and the elephant in the room is addressed.

A high-challenge, high-support approach to performance management dialogue may go like this:

Line manager: David, I wanted to talk as I’ve noticed that some of your work is not up to its normal standard. I had an email saying the report on the Murray contract was a day late and there were two errors in it.

David: What specifically did the email say?

Line manager: It was from Janet who said that she had to chase you three times for cost information and when she received it she had to spend a day reformatting it. This feedback came as a surprise to me. This just doesn’t seem to be what I’ve seen of you in the past. What are your thoughts on this?

David: Yes, sorry, it’s not good enough. I’ll focus more on this in the future.

Line manager: David, what’s behind this?

David: Nothing, all is good. Now I really need to make a phone call.

Line manager: You have plenty of time. I feel that there is something that remains to be discussed, and you seem to be holding back. What is it?

David: OK, I’m bored with the Murray work. I’ve been doing it for 18 months now and it never changes. I feel like I’m in a rut and I’m not progressing.

Line manager: I did not know you felt like this, tell me more.

David: As you know, I’ve been doing some additional work for Sue that’s much more interesting. This is cutting-edge stuff and really plays to my strengths. And I guess I’ve taken my eye off the ball with the Murray work because I’ve lost interest.

Line manager: But we still have the Murray work to do and you’re the project manager; you’re accountable for this. You need to manage this, not just drop it.

David: This isn’t what I signed up for. When you took me on you talked about the opportunity to develop and take on a variety of challenging work. This hasn’t happened.

Line manager: This is clearly a big issue. What do you propose?

David: I don’t want to do the Murray work, and I want to look at the higher-level contracts like the one I’m working on with Sue.

Line manager: I’ll think about what can be done so that you’re involved in the higher-level deals, and also talk to Sue. But I want you to come up with a plan for how we can repair the relationship with Murray’s.

In this dialogue, the line manager addressed this sensitive issue early on before the problems became too large. The line manager did not avoid the issue (the inertia quadrant), hoping it would resolve itself. The line manager went into the zone of uncomfortable debate based on feedback, facts and asking questions to uncover David’s reality. The line manager avoided the stress quadrant and did not blame or accuse based on emotions. The line manager was rational, adult and willing to listen and understand and recognise that David still had much to offer given the right conditions.

Getting the right people is difficult and it is a huge investment to develop them. Line managers should not accept sub-standard performance. However, the way this is managed will determine long-term effectiveness. Inertia or anger will not work.

By balancing support and challenge, using the loving boot and entering the zone of uncomfortable debate, performance management issues can be resolved.

Ian and John’s book ‘Challenging Coaching– Going beyond traditional coaching to face the FACTS’ published by Nicholas Brealey Publishing is available on Amazon. More resources, including a free chapter download can be accessed via www.challengingcoaching.co.uk. This is the third of a monthly column on TrainingZone to explore the detail of challenging leadership.

Ian Day and John Blakey continue their series on challenging leadership. This time, the focus is on performance management.

"We need to get rid of David, he's just not delivering. Sort it out for me" said the director to the human resources manager. In my former career in HR I remember several conversations that started like this. Talking to colleagues who are working in HR today, this type of conversation is still common. But what is going on here? It seems that the performance of an individual has dropped to a low level, issues have not been resolved. The person needs to be fired as the line manager is at the end of his tether. This could lead to an expensive payout and a compromise agreement.

In a similar situation I remember digging to find out what action the line manager had taken. Typically the responsibility for the breakdown in performance could be attributed 50:50 to the employee and line manager. Performance problems usually start when expectations are not explicit, feedback is absent and tricky conversations are avoided. In the example above, I remember the director saying "David is a senior professional, he should know what is expected, I don't have time to spoon-feed him".

So what causes these sort of situations and how can they be avoided?

Consider the 2x2 support challenge matrix and in our example the line manager is in the inertia quadrant; not sure what to do, or too busy and hopes that the problem goes away. This is often followed by movement to the stress quadrant as the line manager loses his/her temper and angrily wants the person out of the business. However the ideal place is high performance high support, the loving boot quadrant of the matrix.

In this quadrant expectations are made explicit, assumptions are surfaced and clarified; difficult conversations are held early, avoiding escalation. The line manager must enter the 'zone of uncomfortable debate’ so that the conversation moves into a more serious and tense discussion, honest feedback is exchanged and the elephant in the room is addressed.

A high-challenge, high-support approach to performance management dialogue may go like this:

Line manager: David, I wanted to talk as I've noticed that some of your work is not up to its normal standard. I had an email saying the report on the Murray contract was a day late and there were two errors in it.

David: What specifically did the email say?

Line manager: It was from Janet who said that she had to chase you three times for cost information and when she received it she had to spend a day reformatting it. This feedback came as a surprise to me. This just doesn’t seem to be what I’ve seen of you in the past. What are your thoughts on this?

David: Yes, sorry, it’s not good enough. I’ll focus more on this in the future.

Line manager: David, what’s behind this?

David: Nothing, all is good. Now I really need to make a phone call.

Line manager: You have plenty of time. I feel that there is something that remains to be discussed, and you seem to be holding back. What is it?

David: OK, I’m bored with the Murray work. I’ve been doing it for 18 months now and it never changes. I feel like I’m in a rut and I’m not progressing.

Line manager: I did not know you felt like this, tell me more.

David: As you know, I’ve been doing some additional work for Sue that’s much more interesting. This is cutting-edge stuff and really plays to my strengths. And I guess I’ve taken my eye off the ball with the Murray work because I’ve lost interest.

Line manager: But we still have the Murray work to do and you’re the project manager; you’re accountable for this. You need to manage this, not just drop it.

David: This isn’t what I signed up for. When you took me on you talked about the opportunity to develop and take on a variety of challenging work. This hasn’t happened.

Line manager: This is clearly a big issue. What do you propose?

David: I don’t want to do the Murray work, and I want to look at the higher-level contracts like the one I’m working on with Sue.

Line manager: I’ll think about what can be done so that you’re involved in the higher-level deals, and also talk to Sue. But I want you to come up with a plan for how we can repair the relationship with Murray’s.

In this dialogue, the line manager addressed this sensitive issue early on before the problems became too large. The line manager did not avoid the issue (the inertia quadrant), hoping it would resolve itself. The line manager went into the zone of uncomfortable debate based on feedback, facts and asking questions to uncover David's reality. The line manager avoided the stress quadrant and did not blame or accuse based on emotions. The line manager was rational, adult and willing to listen and understand and recognise that David still had much to offer given the right conditions.

Getting the right people is difficult and it is a huge investment to develop them. Line managers should not accept sub-standard performance. However, the way this is managed will determine long-term effectiveness. Inertia or anger will not work.

By balancing support and challenge, using the loving boot and entering the zone of uncomfortable debate, performance management issues can be resolved.

Ian and John's book 'Challenging Coaching– Going beyond traditional coaching to face the FACTS' published by Nicholas Brealey Publishing is available on Amazon. More resources, including a free chapter download can be accessed via www.challengingcoaching.co.uk. This is the third of a monthly column on TrainingZone to explore the detail of challenging leadership.