Part two in our series exploring the different models for organisational change Larry Reynolds disects the ‘change equation’ and the ‘change curve.’

In part two of this series we’ll be considering two of the most widely used approaches to change – the change equation and the change curve. The change equation was first articulated by Richard Beckhard and Reuben Harris, based on an idea by David Gleicher.

- D is dissatisfaction with the present

- V is a vision of how things could be

- F is knowledge of the first practical steps

- R is the resistance to change

Change will only occur if D x V x F > R

In other words, people’s natural resistance to (imposed) change will only be overcome by the combined force of dissatisfaction, vision and knowledge of the first practical steps. The model appears in various forms. In Beckhard’s original explanation, F stood for the feasibility of the change, but now more commonly stands for the first practical steps.

In some versions of the equation the factors are added, rather than multiplied together, implying that the absence of, say a clear vision can be compensated by a strong dissatisfaction with the present – a position that proponents of emergent change would probably agree with. Multiplying the three factors implies that if one factor is missing or zero, change probably won’t happen at all. The strengths of the model are its simplicity – even the CEO could understand it – and the fact that it draws attention to the fact that most change initiatives fail because of ‘resistance’; people who simply don’t want the change.

Simplicity is also the model’s weakness. The equation ignores many other factors that are necessary to achieve successful organisational change (getting the right systems and processes in place, for example). It also suggests that the three factors – dissatisfaction, vision, and first practical steps – are somehow equal in weight.

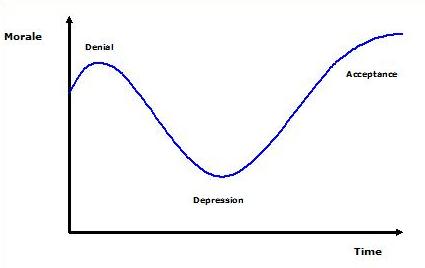

Human beings are much more motivated by the prospect of avoiding loss than they are by the prospect of gain – roughly twice as much according to some studies. This would suggest that dissatisfaction will contribute more to overcoming resistance than vision, an insight often overlooked by change leaders. A good complement to the change equation is the change curve shown below. Originally developed by Elisabeth Kubler-Ross to describe the grieving process, but widely used to describe the emotional stages people go through during organisational change.  When a new change initiative is announced, the initial reaction may be denial – the feeling that it won’t really affect me.

When a new change initiative is announced, the initial reaction may be denial – the feeling that it won’t really affect me.

After a short time the realisation sinks in and depression follows. If the change is well managed, then eventually the change is accepted and morale improves to a slightly higher level than is was before the change began.

The model provides two warnings to change leaders. First, when you announce the change and no one seems that bothered, don’t assume that everything will be rosy in the garden. It’s just that the reality hasn’t sunk in yet. Secondly, accept that almost whatever you do, there will be that dip of depression during the middle of the change: what Bill Bridges calls the neutral zone.

Think carefully about what you can do to bring people through it and into the acceptance stage. The weakness of the model is that it doesn’t tell you what you need to do to manage this dip of depression. The change curve is designed to describe the feelings of people on the receiving end of change. But what about the initiators of change? Are their feelings similar or different? A useful insight is given by the Gartner hype cycle below.

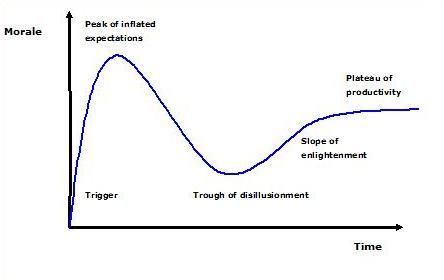

This model was originally developed by consulting firm Gartner Inc to describe the way people respond to new technology. Whereas Facebook and LinkedIn have made it all the way to the plateau of productivity, Second Life doesn’t seem to have come much beyond the peak of inflated expectations it touched a year or two ago. And Twitter – already at the plateau or still at the peak of inflated expectations? You decide!

This model was originally developed by consulting firm Gartner Inc to describe the way people respond to new technology. Whereas Facebook and LinkedIn have made it all the way to the plateau of productivity, Second Life doesn’t seem to have come much beyond the peak of inflated expectations it touched a year or two ago. And Twitter – already at the plateau or still at the peak of inflated expectations? You decide!

This curve also describes rather neatly the expectations of many organisational change leaders. It’s similar in shape to the more widely known Kubler-Ross change curve, but the first peak is higher, reflecting the often over-optimistic views of people driving the change. The end point – the plateau of productivity – is much lower than the peak of inflated expectations.

That’s a useful reminder to CEOs, OD consultants and change leaders everywhere that the end point of change, while beneficial, often does not live up to the initial hype. Like the Kubler-Ross change curve, its strength is that it accurately predicts what will most likely happen during the change process. Its weakness is that it doesn’t tell you how to lead people swiftly through the trough of disillusionment. Perhaps the best advice that can be given to organisational change practitioners is to start small. Pilot things as much as you can and let the results speak for themselves. Avoid the big bang approach where expectations are raised to an unacceptable level.

Other features in the series: The John Kotter leadership model

Larry Reynolds is an organisational change facilitator and managing partner of 21st Century Leader. You can access free resources on leadership, influence and change at www.21stcenturyleader.co.uk.

Part two in our series exploring the different models for organisational change Larry Reynolds disects the 'change equation' and the 'change curve.'

In part two of this series we’ll be considering two of the most widely used approaches to change – the change equation and the change curve. The change equation was first articulated by Richard Beckhard and Reuben Harris, based on an idea by David Gleicher.

- D is dissatisfaction with the present

- V is a vision of how things could be

- F is knowledge of the first practical steps

- R is the resistance to change

Change will only occur if D x V x F > R

In other words, people’s natural resistance to (imposed) change will only be overcome by the combined force of dissatisfaction, vision and knowledge of the first practical steps. The model appears in various forms. In Beckhard’s original explanation, F stood for the feasibility of the change, but now more commonly stands for the first practical steps.

In some versions of the equation the factors are added, rather than multiplied together, implying that the absence of, say a clear vision can be compensated by a strong dissatisfaction with the present – a position that proponents of emergent change would probably agree with. Multiplying the three factors implies that if one factor is missing or zero, change probably won’t happen at all. The strengths of the model are its simplicity – even the CEO could understand it – and the fact that it draws attention to the fact that most change initiatives fail because of ‘resistance’; people who simply don’t want the change.

Simplicity is also the model’s weakness. The equation ignores many other factors that are necessary to achieve successful organisational change (getting the right systems and processes in place, for example). It also suggests that the three factors - dissatisfaction, vision, and first practical steps - are somehow equal in weight.

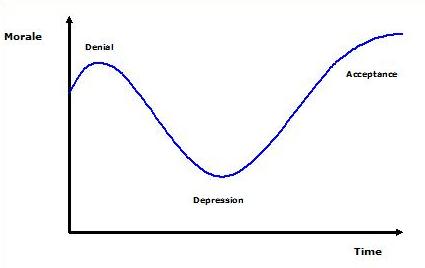

Human beings are much more motivated by the prospect of avoiding loss than they are by the prospect of gain – roughly twice as much according to some studies. This would suggest that dissatisfaction will contribute more to overcoming resistance than vision, an insight often overlooked by change leaders. A good complement to the change equation is the change curve shown below. Originally developed by Elisabeth Kubler-Ross to describe the grieving process, but widely used to describe the emotional stages people go through during organisational change.  When a new change initiative is announced, the initial reaction may be denial – the feeling that it won’t really affect me.

When a new change initiative is announced, the initial reaction may be denial – the feeling that it won’t really affect me.

After a short time the realisation sinks in and depression follows. If the change is well managed, then eventually the change is accepted and morale improves to a slightly higher level than is was before the change began.

The model provides two warnings to change leaders. First, when you announce the change and no one seems that bothered, don’t assume that everything will be rosy in the garden. It’s just that the reality hasn’t sunk in yet. Secondly, accept that almost whatever you do, there will be that dip of depression during the middle of the change: what Bill Bridges calls the neutral zone.

Think carefully about what you can do to bring people through it and into the acceptance stage. The weakness of the model is that it doesn’t tell you what you need to do to manage this dip of depression. The change curve is designed to describe the feelings of people on the receiving end of change. But what about the initiators of change? Are their feelings similar or different? A useful insight is given by the Gartner hype cycle below.

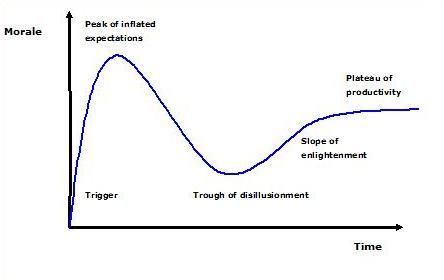

This model was originally developed by consulting firm Gartner Inc to describe the way people respond to new technology. Whereas Facebook and LinkedIn have made it all the way to the plateau of productivity, Second Life doesn’t seem to have come much beyond the peak of inflated expectations it touched a year or two ago. And Twitter – already at the plateau or still at the peak of inflated expectations? You decide!

This model was originally developed by consulting firm Gartner Inc to describe the way people respond to new technology. Whereas Facebook and LinkedIn have made it all the way to the plateau of productivity, Second Life doesn’t seem to have come much beyond the peak of inflated expectations it touched a year or two ago. And Twitter – already at the plateau or still at the peak of inflated expectations? You decide!

This curve also describes rather neatly the expectations of many organisational change leaders. It’s similar in shape to the more widely known Kubler-Ross change curve, but the first peak is higher, reflecting the often over-optimistic views of people driving the change. The end point – the plateau of productivity – is much lower than the peak of inflated expectations.

That’s a useful reminder to CEOs, OD consultants and change leaders everywhere that the end point of change, while beneficial, often does not live up to the initial hype. Like the Kubler-Ross change curve, its strength is that it accurately predicts what will most likely happen during the change process. Its weakness is that it doesn’t tell you how to lead people swiftly through the trough of disillusionment. Perhaps the best advice that can be given to organisational change practitioners is to start small. Pilot things as much as you can and let the results speak for themselves. Avoid the big bang approach where expectations are raised to an unacceptable level.

Other features in the series: The John Kotter leadership model

Larry Reynolds is an organisational change facilitator and managing partner of 21st Century Leader. You can access free resources on leadership, influence and change at www.21stcenturyleader.co.uk.