Written by Roxane Liddell

Watching a toddler negotiate obstacles is fascinating, especially the ‘toy under the table’ scenario. Running full pelt, all the focus is on their favourite toy, not the height of the table … BANG! Need I say more? 10 days later, the same scenario is playing out, but this time upon reaching the table, the toddler ducks.

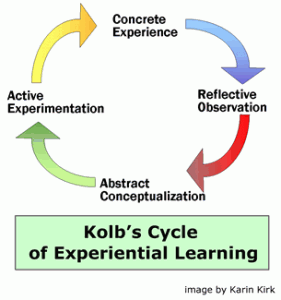

Experiential learning is part of our make-up. John Dewey and Jean Piaget recognised this and advocated that young children learn better through experience. David A Kolb, influenced by these educationalists, took this one step further and, based on his experience in adult education, he created the Experiential Learning Model:

Experiential learning is transformational. Paulo Freire’s work with Brazilian peasant farmers changed their opinion of themselves by helping them to understand who they were via ‘reflection and action on the world in order to transform it.’ Andresen, Boud and Choen (2000) used Kolb’s research to develop their own model of experiential learning and its associated attributes.

To see how e-learning can fit into the cycle, I used a selection of those attributes to explore how experiential learning is harnessed in our e-learning module for Amnesty International on human rights for mental health professionals.

Below is a list of Andresen, Boud and Choen’s attributes with corresponding course features.

The goal of experience based learning involves something personally significant or meaningful to students.

The immersive scenarios we use in the module reflect the real-life experiences of mental health patients. For professionals, these genuine situations offer an opportunity to return to their own experiences. This generates a personal motivation to complete the course: not just to comply with legislation but to improve their practice and ensure better outcomes for their patients.

The whole person is involved, meaning not just their intellect, but also their senses, their feelings and their personalities.

By choosing identifiable narratives, there’s a self-recognition, a familiarity that is instantly recognisable. Learners are emotionally engaged by the scenarios unfolding and the stories recognised from their experiences.The diagnostic at the beginning of the course assesses attitudes, motivations and beliefs. A direct connection is made between the module and their roles and jobs. They have to start thinking and reflecting on their own practice.

Students should be recognised for prior learning they bring into the process.

As part of an opening diagnostic, professionals answer a number of questions, reflecting on how they believe patients should be treated. The output of this is a matrix, which translates those feelings into the four key learning outcomes. The resulting score indicates how far they are already incorporating human rights in their practice.

Reflective thought and opportunities for students to write or discuss their experiences should be ongoing throughout the process.

The action points that professionals can add to their action plan throughout offer a chance to continue this process outside of the module: to discuss and exchange ideas with friends and colleagues. They can print out the action plan at any time, and also contribute their own actions.

According to Kolb, learning is a cycle, where actual experience is refined and improved by reflection. So we shouldn’t look at any e-learning module as a one-off opportunity to make an impact.

Instead, we must look it as a resource, a piece of learning that is constantly returned to as a means of reflecting on lived experience. The new experiences that learners bring on their return should enrich their interactions with the course. Revisiting an e-learning course or platform should feel like the same kind of emotional transaction as returning to well-thumbed book or a favourite DVD.

And why is this so important? Well, we can’t rely on toys and table-tops to teach us all the important lessons forever…

Written by Roxane Liddell

Watching a toddler negotiate obstacles is fascinating, especially the ‘toy under the table’ scenario. Running full pelt, all the focus is on their favourite toy, not the height of the table … BANG! Need I say more? 10 days later, the same scenario is playing out, but this time upon reaching the table, the toddler ducks.

Experiential learning is part of our make-up. John Dewey and Jean Piaget recognised this and advocated that young children learn better through experience. David A Kolb, influenced by these educationalists, took this one step further and, based on his experience in adult education, he created the Experiential Learning Model:

Experiential learning is transformational. Paulo Freire’s work with Brazilian peasant farmers changed their opinion of themselves by helping them to understand who they were via ‘reflection and action on the world in order to transform it.’ Andresen, Boud and Choen (2000) used Kolb’s research to develop their own model of experiential learning and its associated attributes.

To see how e-learning can fit into the cycle, I used a selection of those attributes to explore how experiential learning is harnessed in our e-learning module for Amnesty International on human rights for mental health professionals.

Below is a list of Andresen, Boud and Choen’s attributes with corresponding course features.

The goal of experience based learning involves something personally significant or meaningful to students.

The immersive scenarios we use in the module reflect the real-life experiences of mental health patients. For professionals, these genuine situations offer an opportunity to return to their own experiences. This generates a personal motivation to complete the course: not just to comply with legislation but to improve their practice and ensure better outcomes for their patients.

The whole person is involved, meaning not just their intellect, but also their senses, their feelings and their personalities.

By choosing identifiable narratives, there’s a self-recognition, a familiarity that is instantly recognisable. Learners are emotionally engaged by the scenarios unfolding and the stories recognised from their experiences.The diagnostic at the beginning of the course assesses attitudes, motivations and beliefs. A direct connection is made between the module and their roles and jobs. They have to start thinking and reflecting on their own practice.

Students should be recognised for prior learning they bring into the process.

As part of an opening diagnostic, professionals answer a number of questions, reflecting on how they believe patients should be treated. The output of this is a matrix, which translates those feelings into the four key learning outcomes. The resulting score indicates how far they are already incorporating human rights in their practice.

Reflective thought and opportunities for students to write or discuss their experiences should be ongoing throughout the process.

The action points that professionals can add to their action plan throughout offer a chance to continue this process outside of the module: to discuss and exchange ideas with friends and colleagues. They can print out the action plan at any time, and also contribute their own actions.

According to Kolb, learning is a cycle, where actual experience is refined and improved by reflection. So we shouldn’t look at any e-learning module as a one-off opportunity to make an impact.

Instead, we must look it as a resource, a piece of learning that is constantly returned to as a means of reflecting on lived experience. The new experiences that learners bring on their return should enrich their interactions with the course. Revisiting an e-learning course or platform should feel like the same kind of emotional transaction as returning to well-thumbed book or a favourite DVD.

And why is this so important? Well, we can’t rely on toys and table-tops to teach us all the important lessons forever…