In conclusion to their series on social learning, The Internet Time Alliance finish off by focusing on the theory of return on investment in interaction.

Read part 4 here

Sources of knowhow

Jay Cross’s class at Harvard Business School has the distinction of being the last not allowed to bring portable calculators to exams (A Bowmar 4-function calculator cost $99, a sum that kept many from acquiring one). Today, everyone has several calculators. They’re giveaways. There’s probably one on your phone. All of which makes it irrelevant to learn long division, how to calculate cube roots, or logarithms. Why bother? That’s yesterday’s know-how.

Robert Kelley at Carnegie Mellon discovered that whereas in 1986 we carried 75% of what we need to know to do our jobs in our heads, by 2006 our brains needed to hold only about 8-10% of what we needed to know. The rest is stored in our ‘outboard brains’ – our laptops or, increasingly, our smartphones and in networks.

Once people had to learn most of the things required to do their jobs; now they need to know where to find and retrieve them. They search or ask people when they need to know. If they have a good network of savvy colleagues, they can ask them for advice (‘social search’).

"I store knowledge in my friends"[1]

Instructional designers once only designed instruction. Now they must assess the trade-off of putting knowledge in the worker’s head (learning) or putting it in an outboard brain (performance support).

Among the options available to them:

|

Mainly formal

|

In-between

|

Mainly informal

|

|

Instructor-led class

Workshop

Video ILT

Schooling

Curriculum

|

Mentoring

Conferences

Simulations

Interactive webinars

Performance support

YouTube

Podcasts

Books

Storytelling

|

Hallway conversation

Profiles/locators

Social networking

Trial & error

Search

Observation

Asking questions

Job-shadowing/rotation

Collaboration, Community

Study group

Web jam

Wikis, blogs, tweets, feeds

Social bookmarking

Unconferences

|

Searching and asking questions work best with explicit information; things that could be written down.

The subtle information that cannot be pinned down in simple sentences, for example, the emotions and nuances that make or break a sale, is tougher to transfer because "wisdom can’t be told." [2]

People acquire this implicit knowledge through observing others, collaboration, and lengthy trial and error. Like blindfolded Zen archery [3], mastery sometimes takes years.

Or course, many times we have already learned a skill through experience. Today experiential learning can be accelerated through simulation, virtual worlds, and role play.

|

Mainly Formal

|

Mainly Informal

|

|

|

Control

|

Top-down

|

Laissez-faire

|

|

Delivery

|

Push

|

Pull

|

|

Duration

|

Hours, days, weeks

|

Minutes

|

|

Locus

|

Apart from work

|

Embedded in work

|

|

Author

|

Instructional designer, SME

|

Individual, the learner

|

|

Time to develop

|

Months, weeks

|

Minutes

|

|

When?

|

In advance

|

At time of need

|

|

What?

|

Know

|

Become

|

In the increasingly complex world we inhabit, we often confront novel situations. This requires innovation, a new way of doing things. Innovation is often the result of a mash-up of ideas, for example a rule of thumb from one discipline being applied in a new context.

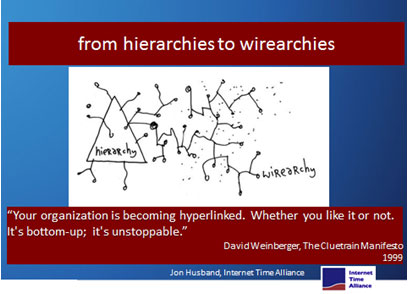

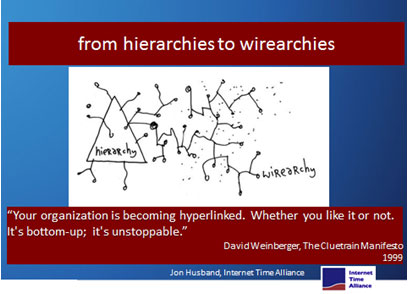

From hierarchies to wirearchy

Wirearchy is the dynamic two-way flow of power and authority based on information, knowledge, trust and credibility, enabled by interconnected people and technology.

The network era now replacing the industrial age holds great promise. Networked organisations are reaping rewards for connecting people, know-how and ideas at an ever-faster pace. Value creation has migrated from what we can see (physical assets) to intangibles (ideas). Look at Google and Cisco.

Understandably, seasoned executives, chief learning officers among them, are having a devil of a time shifting from the industrial age mind-set of logic, certainty and bounded constraints to the network gestalt of interaction, self-organisation, unpredictability and fewer limits to potential. The pressure is constantly on to meet quarter-to-quarter revenue and earnings targets that in turn accentuate the need to take decisions that support achieving those targets. At the same time, we are shifting into an era in which knowledge work and learning occur where re-engineered business processes collide with a participative and interactive ecology of information flows.

How can a chief learning officer hope to make informed judgments in this continually expanding networked environment that’s flowing ever faster, spreading power among its members and producing outsized impacts in unpredictable ways? What to do?

"we are shifting into an era in which knowledge work and learning occur where re-engineered business processes collide with a participative and interactive ecology of information flows."

"we are shifting into an era in which knowledge work and learning occur where re-engineered business processes collide with a participative and interactive ecology of information flows."One cherished industrial age concept that is proving particularly difficult to let go of is return on investment (ROI). But like Pontiacs and Oldsmobiles, old-school ROI’s day in the sun is waning. In an environment of continuous flow and interaction, there’s a need to consider an emerging metric: return on investment in interaction (ROII). The working definition of ROII is the observable development of capacity and capability to create economic values out of intangibles.

The focus in this new world of work is to do what’s important and involve those who know what’s important, why it’s important and what they know (or know how to find out) about a problem or issue. To begin measuring increases in productivity and value in a networked social computing environment, we propose return on investment in interaction (ROII), derived from the principles of Metcalfe’s law of networks.

Some core assumptions about ROII :

- Continuous flows of information are the raw material of an organisation’s value creation and overall performance

- Information flows are carried by links, alerts, RSS feeds, search engines, aggregation and filtering of content

- All leading vendors’ productivity platforms now feature collaborative social networking and computing

- These platforms’ architectures facilitate purposeful cross-silo communications and exchange

Informed judgment

The heart of the matter is providing decision makers with an informed business case that ties investment to the results that it brings. A solid case describes results in business terms, such as increased revenue, better customer service, reduced cost or speedier time to performance.

Network returns are asymmetric, so simplistic count-’em-up approaches are no longer viable. But how can one make a solid network-era case to an executive who is still playing by yesterday’s rules?

The answer is to improve the corporate network as a continuous process, not as a project with a hurdle rate. Improving network performance need not be all-or-nothing. It can be implemented in small stages. Break major decisions into numerous low-risk incremental decisions. Instead of making one major decision a year, CLOs might look at boosting network results as a series of monthly decisions. Continuous monitoring of the statistics of ROII would guide mid-course corrections.

Life was simpler when you could measure performance by counting the number of widgets produced, shipped or sold. Given that the networked workplace and markets are here to stay, how can managers begin to adapt and refocus long-standing mental models about what and where to invest precious energy and time? An effective response to this conundrum is qualitative assessment.

Create a hypothesis and use existing techniques — surveys, focus groups, facilitated brainstorming — to find out what employees and customers are doing and how they want to work together. Then, check it out with a wider sample of the workforce to see if it holds up. It’s clear we are moving rapidly into a networked world in which responsiveness, innovation, gaining competitive advantage through learning faster and embedding knowledge into products and services are all important.

In a world of intangibles, we need to contribute to the productivity, viability and profitability of any given enterprise. We should rethink and expand our methods for making judgments about where, when and how we invest in the on-going interaction between our employees and customers. That is the return on investment in interaction.

citations:

[1] Karen Stephenson, as quoted by Downes

[2]Harvard professor Charles I. Gregg. 1970.

[3]Herrigel, E and Suzuki, D. 1953. Zen and the Art of Archery

[2]Harvard professor Charles I. Gregg. 1970.

[3]Herrigel, E and Suzuki, D. 1953. Zen and the Art of Archery

This article was excerpted from The Working Smarter Fieldbook | September 2010 Edition by Jay Cross, Jane Hart, Jon Husband, Harold Jarche, Charles Jennings and Clark Quinn of the Internet Time Alliance

In conclusion to their series on social learning, The Internet Time Alliance finish off by focusing on the theory of return on investment in interaction.

Read part 4 here

Sources of knowhow

Jay Cross's class at Harvard Business School has the distinction of being the last not allowed to bring portable calculators to exams (A Bowmar 4-function calculator cost $99, a sum that kept many from acquiring one). Today, everyone has several calculators. They're giveaways. There's probably one on your phone. All of which makes it irrelevant to learn long division, how to calculate cube roots, or logarithms. Why bother? That's yesterday's know-how.

Robert Kelley at Carnegie Mellon discovered that whereas in 1986 we carried 75% of what we need to know to do our jobs in our heads, by 2006 our brains needed to hold only about 8-10% of what we needed to know. The rest is stored in our 'outboard brains' - our laptops or, increasingly, our smartphones and in networks.

Once people had to learn most of the things required to do their jobs; now they need to know where to find and retrieve them. They search or ask people when they need to know. If they have a good network of savvy colleagues, they can ask them for advice ('social search').

"I store knowledge in my friends"[1]

Instructional designers once only designed instruction. Now they must assess the trade-off of putting knowledge in the worker's head (learning) or putting it in an outboard brain (performance support).

Among the options available to them:

Mainly formal | In-between | Mainly informal |

Instructor-led class Workshop Video ILT Schooling Curriculum | Mentoring Conferences Simulations Interactive webinars Performance support YouTube Podcasts Books Storytelling | Hallway conversation Profiles/locators Social networking Trial & error Search Observation Asking questions Job-shadowing/rotation Collaboration, Community Study group Web jam Wikis, blogs, tweets, feeds Social bookmarking Unconferences |

Searching and asking questions work best with explicit information; things that could be written down.

The subtle information that cannot be pinned down in simple sentences, for example, the emotions and nuances that make or break a sale, is tougher to transfer because "wisdom can't be told." [2]

People acquire this implicit knowledge through observing others, collaboration, and lengthy trial and error. Like blindfolded Zen archery [3], mastery sometimes takes years.

Or course, many times we have already learned a skill through experience. Today experiential learning can be accelerated through simulation, virtual worlds, and role play.

Mainly Formal | Mainly Informal | |

Control | Top-down | Laissez-faire |

Delivery | Push | Pull |

Duration | Hours, days, weeks | Minutes |

Locus | Apart from work | Embedded in work |

Author | Instructional designer, SME | Individual, the learner |

Time to develop | Months, weeks | Minutes |

When? | In advance | At time of need |

What? | Know | Become |

In the increasingly complex world we inhabit, we often confront novel situations. This requires innovation, a new way of doing things. Innovation is often the result of a mash-up of ideas, for example a rule of thumb from one discipline being applied in a new context.

From hierarchies to wirearchy

Wirearchy is the dynamic two-way flow of power and authority based on information, knowledge, trust and credibility, enabled by interconnected people and technology.

The network era now replacing the industrial age holds great promise. Networked organisations are reaping rewards for connecting people, know-how and ideas at an ever-faster pace. Value creation has migrated from what we can see (physical assets) to intangibles (ideas). Look at Google and Cisco.

Understandably, seasoned executives, chief learning officers among them, are having a devil of a time shifting from the industrial age mind-set of logic, certainty and bounded constraints to the network gestalt of interaction, self-organisation, unpredictability and fewer limits to potential. The pressure is constantly on to meet quarter-to-quarter revenue and earnings targets that in turn accentuate the need to take decisions that support achieving those targets. At the same time, we are shifting into an era in which knowledge work and learning occur where re-engineered business processes collide with a participative and interactive ecology of information flows.

How can a chief learning officer hope to make informed judgments in this continually expanding networked environment that's flowing ever faster, spreading power among its members and producing outsized impacts in unpredictable ways? What to do?

"we are shifting into an era in which knowledge work and learning occur where re-engineered business processes collide with a participative and interactive ecology of information flows."

"we are shifting into an era in which knowledge work and learning occur where re-engineered business processes collide with a participative and interactive ecology of information flows."One cherished industrial age concept that is proving particularly difficult to let go of is return on investment (ROI). But like Pontiacs and Oldsmobiles, old-school ROI's day in the sun is waning. In an environment of continuous flow and interaction, there's a need to consider an emerging metric: return on investment in interaction (ROII). The working definition of ROII is the observable development of capacity and capability to create economic values out of intangibles.

The focus in this new world of work is to do what's important and involve those who know what's important, why it's important and what they know (or know how to find out) about a problem or issue. To begin measuring increases in productivity and value in a networked social computing environment, we propose return on investment in interaction (ROII), derived from the principles of Metcalfe's law of networks.

Some core assumptions about ROII :

- Continuous flows of information are the raw material of an organisation's value creation and overall performance

- Information flows are carried by links, alerts, RSS feeds, search engines, aggregation and filtering of content

- All leading vendors' productivity platforms now feature collaborative social networking and computing

- These platforms' architectures facilitate purposeful cross-silo communications and exchange

Informed judgment

The heart of the matter is providing decision makers with an informed business case that ties investment to the results that it brings. A solid case describes results in business terms, such as increased revenue, better customer service, reduced cost or speedier time to performance.

Network returns are asymmetric, so simplistic count-'em-up approaches are no longer viable. But how can one make a solid network-era case to an executive who is still playing by yesterday's rules?

The answer is to improve the corporate network as a continuous process, not as a project with a hurdle rate. Improving network performance need not be all-or-nothing. It can be implemented in small stages. Break major decisions into numerous low-risk incremental decisions. Instead of making one major decision a year, CLOs might look at boosting network results as a series of monthly decisions. Continuous monitoring of the statistics of ROII would guide mid-course corrections.

Life was simpler when you could measure performance by counting the number of widgets produced, shipped or sold. Given that the networked workplace and markets are here to stay, how can managers begin to adapt and refocus long-standing mental models about what and where to invest precious energy and time? An effective response to this conundrum is qualitative assessment.

Create a hypothesis and use existing techniques — surveys, focus groups, facilitated brainstorming — to find out what employees and customers are doing and how they want to work together. Then, check it out with a wider sample of the workforce to see if it holds up. It's clear we are moving rapidly into a networked world in which responsiveness, innovation, gaining competitive advantage through learning faster and embedding knowledge into products and services are all important.

In a world of intangibles, we need to contribute to the productivity, viability and profitability of any given enterprise. We should rethink and expand our methods for making judgments about where, when and how we invest in the on-going interaction between our employees and customers. That is the return on investment in interaction.

citations:

[1] Karen Stephenson, as quoted by Downes

[2]Harvard professor Charles I. Gregg. 1970.

[3]Herrigel, E and Suzuki, D. 1953. Zen and the Art of Archery

This article was excerpted from The Working Smarter Fieldbook | September 2010 Edition by Jay Cross, Jane Hart, Jon Husband, Harold Jarche, Charles Jennings and Clark Quinn of the Internet Time Alliance[2]Harvard professor Charles I. Gregg. 1970.

[3]Herrigel, E and Suzuki, D. 1953. Zen and the Art of Archery