Usually, when we talk about learning transfer, our desired outcome is that after employees learn something they will utilise that learning to behave differently, not once, but many times. Doing something a significant number of times means we enter the realm of habits. So, let’s look at habits to help us understand how they can both help and hinder us in our quest for learning transfer.

What is a habit?

A simple definition of a habit is that it is something we do often and regularly, perhaps without even being aware of the fact that we are doing it. Habits have a sense of the automatic about them and as a result they are difficult to stop or give up.

In our day-to-day lives we are acutely aware of habits and how they impact on us either getting or not getting what we want in life. This has spawned a huge branch of the self-help and personal development industry; if you do a search for ‘habits’ on Amazon, you get over 20,000 results in the books section.

Our brains are fundamentally lazy, or efficient depending on your point of view, and create automated pathways by wiring together thoughts, emotions and behaviours so these can then be run on autopilot.

Changing a habit is ‘expensive’ and retaining an old habit is ‘cheap’ in terms of both cognitive and emotional load.

These automated habit pathways come online and offline throughout the day in response to situational triggers, usually with little conscious awareness. If we are aware of them, we tend to classify habits as good or bad, depending on whether we consider them beneficial to us or not, but most habits are neutral.

They are called into play as we go through our morning ritual, as we leave the house for work, as we seek out a car parking space and as we travel the same route through the supermarket aisles each time we go shopping.

All habits have some basic similarities

They are:

-

Created by repetition.

-

Triggered in response to a cue.

-

Performed automatically, often with little conscious awareness.

-

Persistent and hard to not do in response to the cue.

There is an old Spanish proverb, ‘habits are at first cobwebs, and then they become cables’.

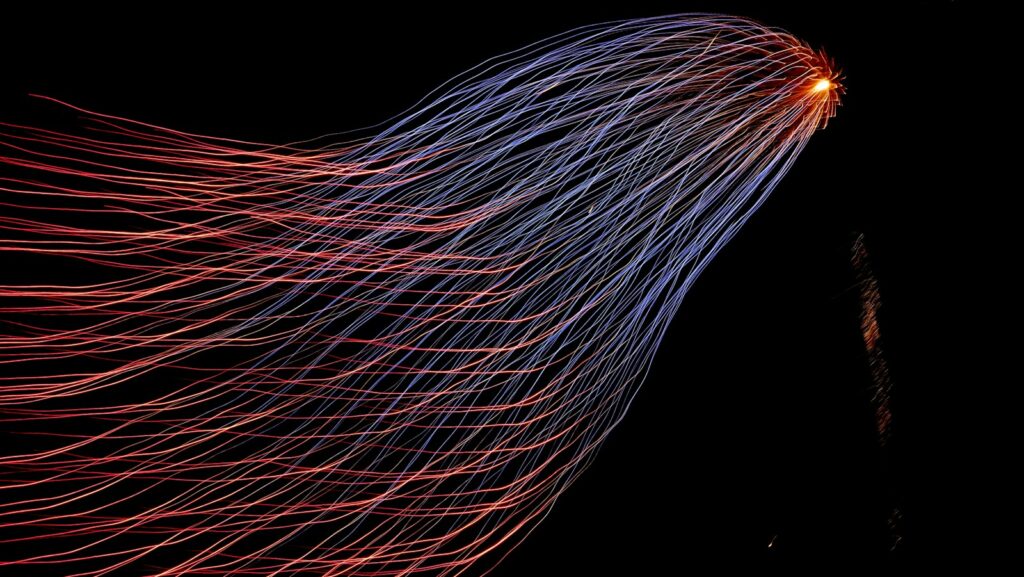

When an activity is repeated many times, the neurons that make up the circuits in the brain that drive the activity become more strongly linked. The neurons physically change, which is referred to as brain plasticity, and the neuronal circuit for the activity becomes more stable.

This effect has been popularised in the expression ‘cells that fire together wire together’. The concept was first introduced by Donald Hebb in his 1949 book, The Organization of Behaviour, and is often referred to as Hebb’s rule.

It is clear from this that a habit cannot form without repetition, and the more repetition there is, the more ingrained and stable in our neurology the habit becomes. It is this stability that makes a habit so useful when it is a ‘good’ habit, and so destructive when it is a ‘bad’ habit.

The difficulty with creating new habits

On the face of it, creating a new habit seems simple enough and the self-help literature would have us believe this is so.

To create the new habit, decide on the situation or cue you want to use as the trigger, and then discipline yourself to do the new behaviour many, many times in response to the cue.

Jim Rohn, a renowned motivational speaker said, “repetition is the mother of skill”. The complication, however, is that most things that we do during our day are habitual, so it would be very rare for us to be in a situation where we are creating a new habit that has no conflict with an existing one.

According to CEOS theory, the conflict that arises when we try to create a new habit is between the two overarching systems within the brain that control behaviour: executive and operational. CEOS is an acronym for context, executive and operational systems and the theory seeks to explain the limits of rational choice on behaviour modification.

The executive system controls behaviours such as planning, reasoning, problem solving, making judgments and weighing alternatives, all of which require conscious thought and cognitive control.

The difficulty of giving up an undesirable but attractive behavioural habit is typically the greatest barrier to change

It is top-down in operation and requires internal dialogue and therefore language. The operational system operates at an unconscious level to manage activities, such as walking and talking, that allow us to go about our day without having to think about them unduly.

It is bottom-up in operation and is reflexive and automatic in a way that does not require language.

These two systems operate together to produce our behaviour, but when we seek to introduce behavioural change, especially changes to habituated behaviour, it introduces conflict between these two systems.

Changing a habit requires the executive system to override the operational system over extended periods of time and many repetitions, and this in turn requires extended and high levels of effort and attention. The ongoing conflict and dissonance generate negative emotional responses: it just doesn’t feel good. Changing a habit is ‘expensive’ and retaining an old habit is ‘cheap’ in terms of both cognitive and emotional load.

The role of emotions in changing habits

The idea of there being two quite different processes guiding human behaviour is not new.

The Buddha used the metaphor of the rider on the elephant. The rider is the executive system and it can’t force the elephant to do what the rider wants. The rider needs to create conditions, through training, that lead the elephant to want what its rider wants. The rider needs to be clever enough to harness and manage the power of the elephant.

Our feelings and emotions impact our ability to create or change habits. Negative emotion is a signal that something is wrong and therefore remedial action is required to fix the situation and avoid the negative emotion.

Positive emotions, on the other hand, indicate there is no reason for concern and the current situation can be allowed to continue. What this means is that there is little incentive for us to pursue effortful behaviours, such as the effort of the ES overriding the OS to repeat a new desired behaviour, when we are already feeling good.

Unfortunately, there is no negative emotional signal to us when we relapse and repeat the old, undesired behaviour. All we can do, after the fact, is berate ourselves for our lack of self-discipline and accepting the short-term reward of doing what we used to do.

The difficulty of giving up an undesirable but attractive behavioural habit is typically the greatest barrier to change, and thus to achievability.

Achievability can sometimes be at least partly conceived of as overcoming the desirability of the problematic behaviour. How can you reframe the old habit so that it is not so attractive in the moment?

One way is to plug into our greater desire to avoid loss rather than achieve gain. Telling people what they will lose by continuing an existing behaviour is a more powerful way to offset the comforting continuance of that behaviour than trying to educate them on what they will gain by switching behaviours.

Some commentators say that you can’t actually break a habit, but you can mask it by attaching a different routine to the same trigger to give an equivalent or better reward, and then doing that routine over and over again until it becomes automatic.

This article is an excerpt from Paul Matthews’ book, Learning Transfer at Work: How to Ensure Training >> Performance.

Interested in this topic? Read Learning transfer: why we need to see learning as a pathway, not an event.

Usually, when we talk about learning transfer, our desired outcome is that after employees learn something they will utilise that learning to behave differently, not once, but many times. Doing something a significant number of times means we enter the realm of habits. So, let’s look at habits to help us understand how they can both help and hinder us in our quest for learning transfer.

What is a habit?

A simple definition of a habit is that it is something we do often and regularly, perhaps without even being aware of the fact that we are doing it. Habits have a sense of the automatic about them and as a result they are difficult to stop or give up.

In our day-to-day lives we are acutely aware of habits and how they impact on us either getting or not getting what we want in life. This has spawned a huge branch of the self-help and personal development industry; if you do a search for ‘habits’ on Amazon, you get over 20,000 results in the books section.

Our brains are fundamentally lazy, or efficient depending on your point of view, and create automated pathways by wiring together thoughts, emotions and behaviours so these can then be run on autopilot.

Changing a habit is ‘expensive’ and retaining an old habit is ‘cheap’ in terms of both cognitive and emotional load.

These automated habit pathways come online and offline throughout the day in response to situational triggers, usually with little conscious awareness. If we are aware of them, we tend to classify habits as good or bad, depending on whether we consider them beneficial to us or not, but most habits are neutral.

They are called into play as we go through our morning ritual, as we leave the house for work, as we seek out a car parking space and as we travel the same route through the supermarket aisles each time we go shopping.

All habits have some basic similarities

They are:

Created by repetition.

Triggered in response to a cue.

Performed automatically, often with little conscious awareness.

Persistent and hard to not do in response to the cue.

There is an old Spanish proverb, 'habits are at first cobwebs, and then they become cables'.

When an activity is repeated many times, the neurons that make up the circuits in the brain that drive the activity become more strongly linked. The neurons physically change, which is referred to as brain plasticity, and the neuronal circuit for the activity becomes more stable.

This effect has been popularised in the expression 'cells that fire together wire together'. The concept was first introduced by Donald Hebb in his 1949 book, The Organization of Behaviour, and is often referred to as Hebb’s rule.

It is clear from this that a habit cannot form without repetition, and the more repetition there is, the more ingrained and stable in our neurology the habit becomes. It is this stability that makes a habit so useful when it is a ‘good’ habit, and so destructive when it is a ‘bad’ habit.

The difficulty with creating new habits

On the face of it, creating a new habit seems simple enough and the self-help literature would have us believe this is so.

To create the new habit, decide on the situation or cue you want to use as the trigger, and then discipline yourself to do the new behaviour many, many times in response to the cue.

Jim Rohn, a renowned motivational speaker said, “repetition is the mother of skill”. The complication, however, is that most things that we do during our day are habitual, so it would be very rare for us to be in a situation where we are creating a new habit that has no conflict with an existing one.

According to CEOS theory, the conflict that arises when we try to create a new habit is between the two overarching systems within the brain that control behaviour: executive and operational. CEOS is an acronym for context, executive and operational systems and the theory seeks to explain the limits of rational choice on behaviour modification.

The executive system controls behaviours such as planning, reasoning, problem solving, making judgments and weighing alternatives, all of which require conscious thought and cognitive control.

The difficulty of giving up an undesirable but attractive behavioural habit is typically the greatest barrier to change

It is top-down in operation and requires internal dialogue and therefore language. The operational system operates at an unconscious level to manage activities, such as walking and talking, that allow us to go about our day without having to think about them unduly.

It is bottom-up in operation and is reflexive and automatic in a way that does not require language.

These two systems operate together to produce our behaviour, but when we seek to introduce behavioural change, especially changes to habituated behaviour, it introduces conflict between these two systems.

Changing a habit requires the executive system to override the operational system over extended periods of time and many repetitions, and this in turn requires extended and high levels of effort and attention. The ongoing conflict and dissonance generate negative emotional responses: it just doesn’t feel good. Changing a habit is ‘expensive’ and retaining an old habit is ‘cheap’ in terms of both cognitive and emotional load.

The role of emotions in changing habits

The idea of there being two quite different processes guiding human behaviour is not new.

The Buddha used the metaphor of the rider on the elephant. The rider is the executive system and it can't force the elephant to do what the rider wants. The rider needs to create conditions, through training, that lead the elephant to want what its rider wants. The rider needs to be clever enough to harness and manage the power of the elephant.

Our feelings and emotions impact our ability to create or change habits. Negative emotion is a signal that something is wrong and therefore remedial action is required to fix the situation and avoid the negative emotion.

Positive emotions, on the other hand, indicate there is no reason for concern and the current situation can be allowed to continue. What this means is that there is little incentive for us to pursue effortful behaviours, such as the effort of the ES overriding the OS to repeat a new desired behaviour, when we are already feeling good.

Unfortunately, there is no negative emotional signal to us when we relapse and repeat the old, undesired behaviour. All we can do, after the fact, is berate ourselves for our lack of self-discipline and accepting the short-term reward of doing what we used to do.

The difficulty of giving up an undesirable but attractive behavioural habit is typically the greatest barrier to change, and thus to achievability.

Achievability can sometimes be at least partly conceived of as overcoming the desirability of the problematic behaviour. How can you reframe the old habit so that it is not so attractive in the moment?

One way is to plug into our greater desire to avoid loss rather than achieve gain. Telling people what they will lose by continuing an existing behaviour is a more powerful way to offset the comforting continuance of that behaviour than trying to educate them on what they will gain by switching behaviours.

Some commentators say that you can’t actually break a habit, but you can mask it by attaching a different routine to the same trigger to give an equivalent or better reward, and then doing that routine over and over again until it becomes automatic.

This article is an excerpt from Paul Matthews' book, Learning Transfer at Work: How to Ensure Training >> Performance.

Interested in this topic? Read Learning transfer: why we need to see learning as a pathway, not an event.